Section 3 of "A Defense of Bestiality"

Let’s workshop--for National Interspecies-Sex Month--the third section of an essay that aims to defend the moral permissibility of bestiality under certain circumstances

Sections 1 and 2 can be found here.

A Defense of Bestiality

Dedicated to Gary Varner

3. Intuitive Case Against Bestiality

3.1. Argument

One common reason cited for the moral impermissibility of bestiality is that it is just intuitively wrong. It shows in our immediate disgust. It shows in that questioning the permissibility of bestiality merely from intellectual curiosity is triggering enough to rouse ire and violence—as I know personally, having done so once at a playdate barbecue. Even progressive books on abnormal psychology, those which tell empathetic stories as to how someone came to be open to sexual activity with animals, cannot help but state what used to be stated about homosexuality: that such an orientation, even if compassion-deserving, is too vile to be left untreated.[i]

The basic argument from intuition, then, should be clear.

1. If it is intuitive that bestiality is morally impermissible, then bestiality is morally impermissible.

2. It is intuitive that bestiality is morally impermissible.

Therefore, bestiality is morally impermissible.

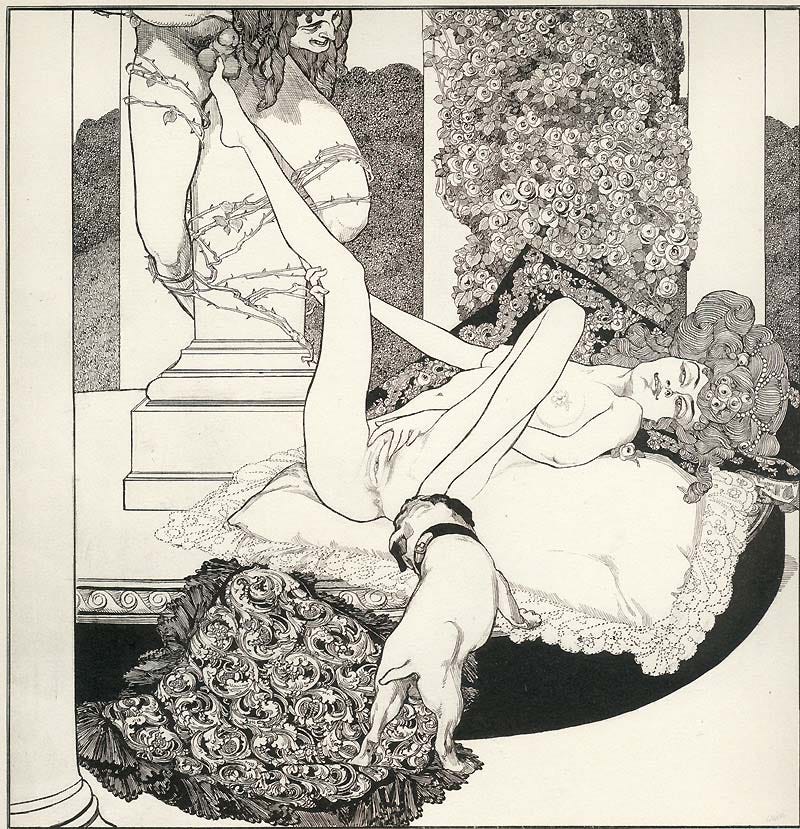

As much as admitting it might seem to undermine my case, I too find it disgusting to envision someone, say, performing fellatio on a horse (the preferred animal, second only to dogs, in human-animal sexual contact). If I picture myself taking a pig from behind, it is hard not to feel nauseous (even if the pig is fully enjoying the interaction with one of its renowned thirty-minute orgasms). No doubt I get at least semi-erect when I think of the women of ancient Rome who would train snakes “to coil around their thighs and slide past the lips of their vaginas.”[ii] But that is mainly because I am homing in on the human’s sexual organ and, if anything, reducing the penetrating entity to something more like a dildo. For whatever it might be worth, I do wish I were liberated enough not to feel the repulsion. But I cannot help it. Might there be, as Leon Kass or Clive Hamilton would say, ethical insight in my indelible repugnance? Might my disgust be my conscience telling me that bestiality is immoral?[iii]

3.2. Response

The argument from intuition, I sense, is the core reason for our strident rejection of bestiality. The first thing one experiences if one questions the rationality of the taboo is, if not a fist or a glass thrown one’s way, the indignant exclamation “Animals can’t consent!” It is intriguing how these same individuals almost always ignore the issue of consent when it comes to confining animals in cramped cages or slaughtering them for consumption—yes, even in our no-excuse era of the so-called “impossible burger.” Funny enough, the mother of my son’s friend at the aforementioned playdate—after yelling “Do you wanna fuck my dog, you pig!”—threw her burger at me (missing) in what would have been a total waste of factory-farmed kill were it not for my liberal-Mississippi interpretation of the five-second rule. What I really think is going on is that all the gum-flap about consent, an issue I will get to section 6, is just a righteous-sounding veneer over what is ultimately a gut reaction of disgust. Disgust drives our condemnation.[iv]

The argument from intuition can be quickly put aside, though. This line of reasoning suffers from some obvious deficiencies.

Let us begin by looking at the problems surrounding premise 2.

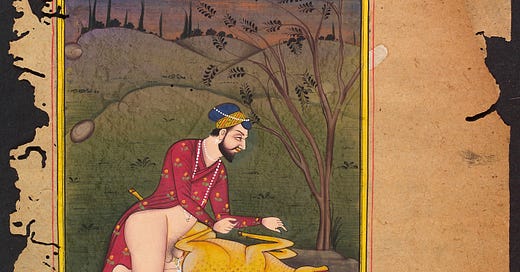

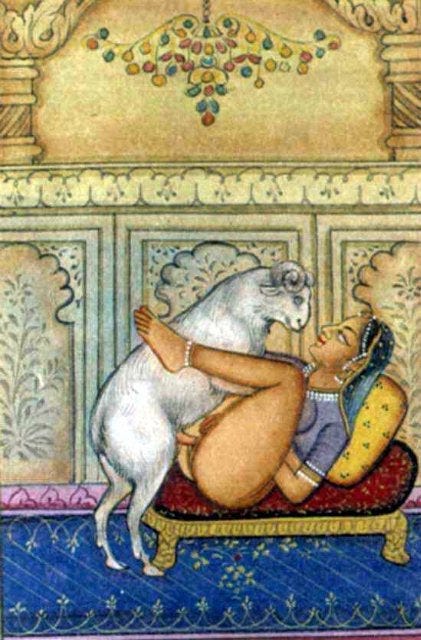

(1) Our intuitions against bestiality are by no means universal. It was not uncommon in ancient Egypt for women to have sex with dogs and men to have sex with cattle. Or think of the ancient Greeks who regularly practiced sex beyond the species divide (especially during religious celebration). Think of the ancient Hindus who captured their widespread sexual activity with animals in temple art across India. Think of the Kisii people of Kenya who regard sex with animals as normal in adolescence. Think of the Masai teens who use donkeys to satisfy their needs and hone their sexual competence. Think of the “Comeburras” of Colombia who, starting around seven, have sexual interactions with female donkeys. Think of the Inuit peoples who, male and female alike, have been known to engage in sexual contact with dogs in particular. Think of those North Costa Rican tribes who, although banning sex with dogs, see sex with donkeys and pigs as no biggie. Think of the Matis men of the Amazonian rainforest who prize sloths as sexual mates. Think of the youths of Crete and Cyprus who, up until the 1980s, would practice their sex skills with donkeys, goats, pigs, and birds. Think of the Yoruba of Nigeria who would commemorate their first antelope kill by having sex with it. Think of the Crow Indians of Montana who were known to have sex with the animals they killed too. Think of Beirut in the 1960s, which was known as a bestiality hotspot (close to that of the biblical land of Canaan). Think of the Babalonian orgies involving dogs during the Spring Fertility Rites. Think of the Tamils of Sri Lanka and their relations with cows and goats. Think of Thailand or Taiwan and their human-animal sex shows (which purportedly put to shame the famous donkey shows in mid-twentieth century Mexico). Think of the Hopi tribe, the Sioux tribe, the Apache tribe, the Mohave tribe. The list goes on and on, back into a prehistory of art—cave paintings, carvings—that reflect a people with, let us just say, much less hangups around sexual pleasure.[v] So no, not everyone feels intuitive disgust toward bestiality. Some find it as welcoming as I find performing analingus on my (human) girlfriend. No doubt this is true for at least some of history’s famous animal lovers: Tiberius (and his wife), Claudius, Nero, Constantine the Great, Eudoxia, Catherine the Great, Giles de Rais, Thomas Grainger, Thomas Weir, King Edward II, Aleister Crowley, Larry Flynt—to name but a few. Perhaps this explains why between 1630 and 1778 around 700 people were executed for bestiality in Sweden alone. It has got to be delectable for some if it is worth the risk of being slain like homosexuals in a bonfire by the government (sometimes after drawn-out torture in the town square)![vi] Even if the paranoia from which it springs is overblown, why else would the Talmud—in perfect alignment with the Papua-New-Guinean maxim “No one likes a dog better than a woman”—demand that widows get rid of their sexually-tempting pet dogs? Why else would the colonial government in Plymouth list bestiality as grounds for divorce? Bracketing off, of course, the pervy eagerness to masturbate to taboo tales behind the penitential screen, why else would it have been so standard (up unto the 1960s) for priests in France and Poland and Sicily to ask during confession whether there had been any use of animals for sex? Why else would there be bestiality magazines such as The Wild Animal Revue whose advertisements include dildos shaped in the form of various animals?[vii]

(2) However unshakably gross it seems to me, I find it intuitive—well, intellectually intuitive—that bestiality is morally permissible under the right circumstances (see sections 2 and 8). Premise two, then, is false as far as I am concerned. I have felt this way since I was a teenager. It has been a strong enough belief that I have always used it, along with some other measures, to filter out potential long-term mates. If a woman could see no way in which certain forms of bestiality could be morally acceptable, then that was a hard boundary for me.

(3) Our intuitive response to bestiality could shift in the future. Just as our repulsion toward homosexuality and miscegenation diminished as it became more accepted in society, it is plausible that our repulsion towards bestiality would diminish if it became more accepted (like, say, in rural Sicily in the 1940s or parts of Denmark just a decade ago).[viii] It seems likely that with greater exposure to people who engage in bestiality (friends and family, in particular), our disgust will give way to a nuanced understanding and acceptance—perhaps even a new breed of look-who’s-coming-to-dinner films. It is hard to see why it would not, especially when it comes to the obviously nonproblematic instances embodied in Cases 7-9.

The most devastating problems, however, concern premise 1.

(1) It is crucial to consider whose gut intuitions we are relying on when evaluating the moral permissibility of bestiality: the gut intuitions of humans. But we are the sort of critters who can bomb a village full of infants from afar with little problem and yet who crumble when it comes to shooting just one in the head up close—and even if it will save all the others. We are the sort of critters who are fine with kids watching people get stabbed and shot and blown up and poisoned each day on TV and yet who restrict them from seeing a nipple flash across the screen as if their souls depended on it. We are the sort of critters who eat factory-farmed meat and even joke about it and trivialize the ethical concerns surrounding it, as in when our beloved Chick-fil-A commercials depict cows begging us, in lighthearted mercy, to “Eat Mor Chikin.” We are the sort of critters who placidly take in hunks of veal and chicken and pig into our mouths and yet insist that eating cat or dog or horse meat is morally reprehensible. We are the sort of critters who impose laws against photographing animals and children together in any manner that could be even remotely deemed sexual and yet who sponsor afterschool programs to teach children how to stimulate female cows through teat massage and spanking and fingering to make them receptive to semen. We are the sort of critters who once found it a core intuition, an unshakeable conviction, that what goes up must come down, that the Earth stands still, that the Earth is flat, that the Earth is the center of the universe, that people can rise from being long dead, that this wafer is the literal body of Christ, that personality traits can be discerned through skull contours, that prayer can cure the illness of a stranger on the other side of the world, that certain stones can cure cancer and bring wealth into your life, that a sky God judges each of us for how many times we shake after we pee, that the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine causes autism (rather than simply being correlated with the time around which diagnoses are most likely to be first made), and so forth. We are the sort of critters who often exhibit cognitive biases that can hinder rational thinking and decision-making: favoring information that confirms preexisting beliefs (confirmation bias) or making decisions—such as not to fly—based on recent or easily-accessible examples like news of a plane crash (availability heuristic). We are the sort of critters who often prioritize short-term benefits over long-term consequences: poisoning the air and sea and land for quick profits; overeating and overfishing and overlogging despite the tumultuous impact not only to other creatures but to humans themselves. We are the sort of critters who often act on reason-clouding emotions (impulsively buying things we neither need nor can afford; hastily deciding on a course of action based on fear rather than evidenced-based analysis). We are the sort of critters who, given our limits in duration and knowledge and power, form generalized assumptions about entire groups of people based on their most superficial characteristics and without even much exposure to individuals that might be said to belong to those groups. We are the sort of critters who have a tough time understanding even people of the same language, preferring to see in their words what we want to see rather than what is really there. We are the sorts of critters who die in droves convinced that God is on our side of the war. We are the sort of critters—selfish and power-hungry—who exhibit an intense resistance to change, preferring the familiar and comfortable (Jesus rose from the dead, Earth is flat) no matter the evidence to the contrary—indeed, even ready to kill others who threaten to question our taboos or call us out on our hypocrisies (which is a central reason why it would be hard to place a paper like this in a mainstream philosophy journal).

(2) There are various examples of behaviors that the majority regarded as intuitively immoral but clearly are not. Homosexuality serves as a poignant example. Even today I would feel uneasy, although it does shame me to admit it, if I stumble upon male-male pornography. And the mere thought of being in hardcore situations with another man elicits within my gut queasy revulsion. Just as in the case of bestiality, I do wish I were more liberated. But it would be intellectually unsound, and downright barbarity, for me to conclude that because I feel such disgust, and because the majority of my society feels such disgust (let us imagine this is taking place a hundred years ago), homosexuality must be morally impermissible. The same goes for bestiality.

(3) Claims of what is intuitive cannot settle debates in philosophy classrooms. This is clear even when we push aside the fact that initial gut reactions and intuitive repulsions can be influenced by cultural biases and societal conditioning. After all, people on each side of the core philosophical issues (whether God exists, whether human moral freedom is compatible with determinism, whether abortion is morally permissible, and so on) have equally ingrained intuitions. If intuition alone could settle the matter, that would imply what is logically untenable: for instance, that God exists in the very same respect in which God does not exist. To be sure, all other things being equal between two competing positions (equal in respect to parsimony, explanatory power, or so on), we go with the one that aligns best with the intuitions of the majority. But as I make clear in the rest of this paper, all other things are not equal between my view (that sometimes bestiality can be morally permissible) and the competing view (that bestiality can never be morally permissible).

3.3. Conclusion

Merely citing our personal gut, even when that gut wretches, is insufficient to establish the moral impermissibility of bestiality. More impersonal justification is needed. Look at it this way. Presumably kicking infants in the head for the fun of it is wrong, if it is at all, not at root because our intuition says so. Instead of being, in effect, the arbitrary decree of our intuition, the direction of explanation goes the other way around: our intuition says kicking infants in the head is wrong because doing so is wrong, wrong according to facts independent of whatever our intuition says. The opponent of bestiality, therefore, needs to needs to disclose what these facts are in the case of bestiality.

Notes

[i] See Rudy 2012, 607.

[ii] Miletski 2005.

[iii] See Kass 1997; Hamilton 2008. Hamilton, following Schopenhauer, argues that our intrinsic visceral disgust points to the fact that bestiality is an offense to the metaphysical differences between species. The idea is that we feel an abstract pain even to hear about cases of bestiality because platonic categories, set in the stone of eternity, are being muddied in such cases. The problem, of course, is that people could give—and, indeed, have given—“explanations” like this for why, say, miscegenation is wrong.

[iv] Haynes puts the point well. “The refusal to give consideration to whether an animal consents to other uses suggests that the consent argument may be a cover for unreflective disgust—an effort to disallow sex with animals while still permitting more popularly considered “important and innocuous” uses of animals, like hunting, raising them for food, and using them for transportation” (2014, 130n44).

[v] See Holoyda 2022; Valcuende del Rio and Caceres-Feria 2020, section 3; Miletski 2005.

[vi] Liliequist 1991, 394; Miletski 2005. To be sure, these people—although countless—are all in the minority, so at least I presume. That said, we might be surprised by what we see when we stick a plethysmograph on the genitalia of the most vanilla of us while we read of Catherine the Great’s purported exploits with horses.

[vii] Miletski 2005; Masters 1966.

[viii] Miletski 2005; Masters 1966.

This essay is unpublished