Sections 1 and 2 of "A Defense of Bestiality"

Let’s workshop--for National Interspecies-Sex Month--the first two sections of an essay that aims to defend the moral permissibility of bestiality under certain circumstances

A Defense of Bestiality

Dedicated to Gary Varner

If you include in bestiality only people who have sex exclusively with animals, then the percentage of course falls far below 1 per cent. On the other hand, if you drop the requirement that for sexual contact something has to be inserted somewhere and that something has to be fiddled with, and it is sufficient simply to cuddle, to derive a warm feeling from each other, to kiss perhaps at times, in brief to love, then bestiality is not a deviation but the general rule, not even something shameful, but the done thing. After all, who does not wish to be called an animal lover?[i]

1. Introductory Remarks

Rare it is to come across someone who would argue openly for the moral permissibility of bestiality, the sexual contact between human and nonhuman animals.[ii] The prevailing view is that bestiality is immoral under all circumstances. The central rationale has long been that bestiality debases our special dignity as humans, tarnishes our privileged status as deliberative agents whose rationality frees us from the instincts that puppeteer animals. In our era of animal-rights activism, this rationale has been reinforced by the notion that animals have inherent moral worth and so should not be subject to indignities and cruelties.[iii]

I contend, on the contrary, that under certain circumstances sexual activity with animals is morally permissible. Especially when the wants and welfare and moral worth and autonomy of all parties are respected, especially when the interaction is voluntary and non-distressing and non-exploitative and mutually enjoyable and mutually opt-out-able, bestiality is merely a benign form of nontraditional living. It is much more benign, in fact, than many popular practices whose moral permissibility largely remains unquestioned: grooming animals to serve as our tools and playthings, or castrating them into docility, or fondling their teats and vaginas to get them in the breeding mood while tied up to what are known as “rape racks,” or sticking electric rods up their rectums to produce reliable ejaculations—or, of course, putting them through literal meat grinders and then onto our grills.

The burden of proof, I take it, falls upon me—yes, despite the fact that most of us regard as unproblematic various barbarities inflicted upon animals, even when they dissent through skin-crawling screams and heart-wrenching attempts to flee. Although sexual activity with animals has been happening as long as humans have been around, and although pro-bestiality organizations and forums are gaining popularity in the digital age (especially in progressive countries like Germany, Denmark, and Norway), bestiality remains condemned across a variety of cultures.[iv] Laws prohibiting sexual contact between humans and animals, which range back to the Hittites in 1650 BCE, are widespread across western nations (with noted exception of Hungary and a few other countries). These laws have become increasingly stringent especially in the US since the turn of the millennium, where such contact—unless carried out for husbandry or veterinary or research or educational purposes—is an offense in all states except New Mexico and West Virginia (some of which—like Texas and Florida—have laws according to which the mere observing of bestiality is a criminal offense).[v]

There are enticing reasons behind the longstanding criminalization of bestiality. Bestiality violates our intuitions concerning right and wrong while also seemingly violating both the commands of the Abrahamic God and the so-called “natural way of things” (issues I discuss in sections 3 through 5). Cutting even deeper than that, many argue that bestiality endangers both animal and human welfare (issues I discuss in sections 6 and 7).

However compelling these reasons might seem, my intention is to show that—perhaps in some sense reflecting how often in history lawmakers banned bestiality in the same breath not only as masturbation and anal sex, but also as witchcraft and sorcery[vi]—solid foundation is lacking for our moral opprobrium here. By no means do I intend to promote bestiality. I simply hope to bring into relief the possibility of humans and animals engaging in morally unproblematic sexual interactions.

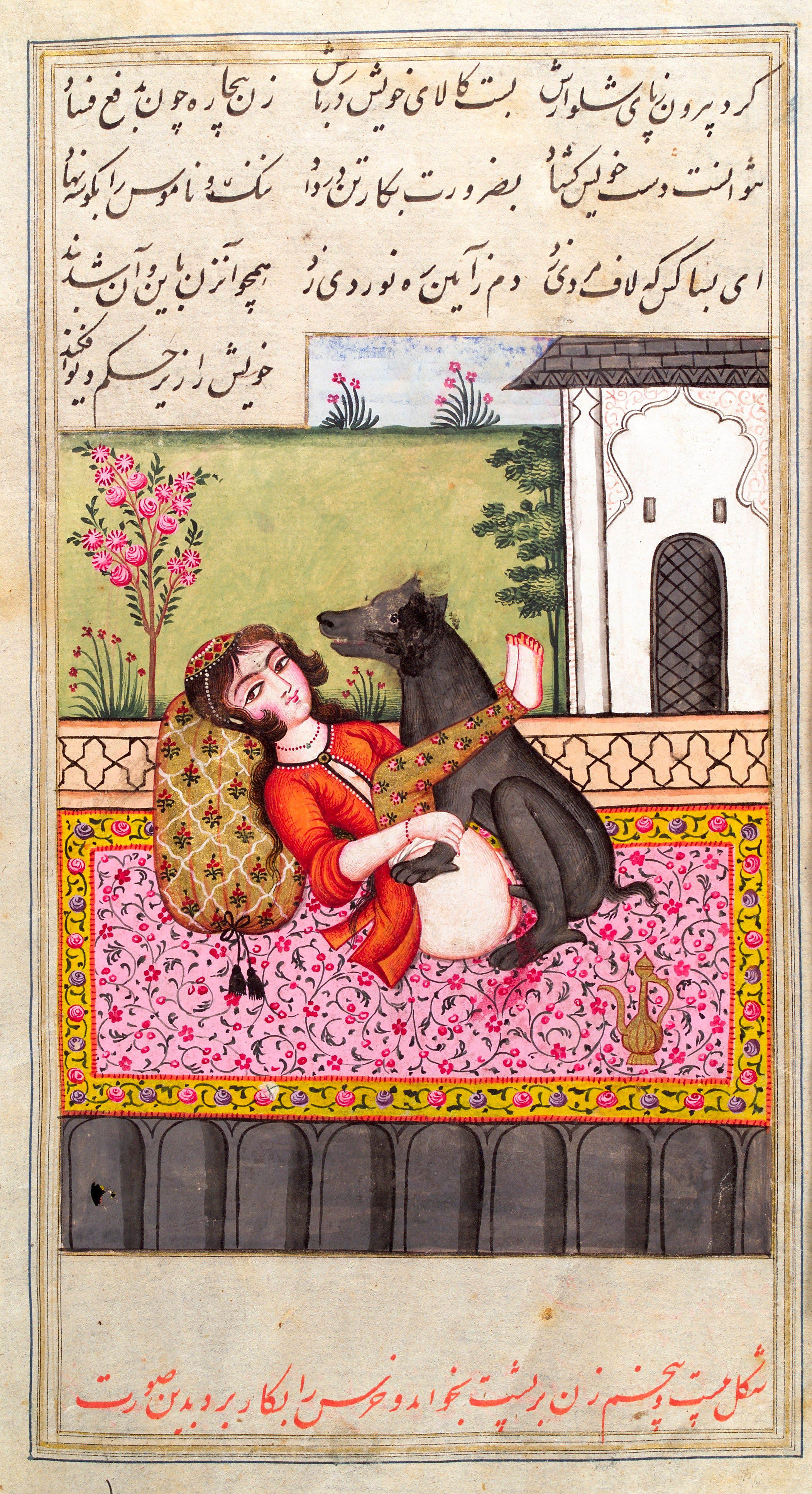

2. Cases of Bestiality

Not all instances of bestiality are morally permissible, at least I am willing to grant. This should be clear by considering the following array of cases, which serve as touchstones throughout the essay.

A. Cases where the sexual activity is coerced, cruel, and harmful

Case 1.—A man pound-towns away violently up the egg hole of a hen squawking in her vain attempts to fly away—ultimately, so that the involuntary contractions of her traumatic dying align with his climax, wringing her neck (a technique known to have been used on turkeys by the French and on geese by the Chinese).[vii]

Case 2.—A woman covers her vagina in peanut butter after starving her border collie and then, after it has licked her clean and tries to move away, forces its snout into her—back and forth—despite its desperate yelps for breath.

Case 3.—Unable to control the piglet enough to get his penis inside its rectum and yet not wanting to resort to the ground-smash move of the factory farm (since his parents keep a tight inventory on the number of pigs), a teen boy drugs it into complacency first.

B. Cases where the animal is neither aware of sexual activity nor sexually stimulated

Case 4.—Vulvic wetness and engorgement chronic over the recent weeks, a tween girl—who, by the way, has a strong bond with her horse and only rides him when he wants to ride—has been enjoying galloping on his back because his gyrations readily bring her to climax.

Case 5.—In line with more rural men than one might think over the centuries, a farmhand utilizes the suckling reflex of a calf to receive a so-called “Kansas milking” (pulling out during climax because he could not locate a definitive Reddit or ChatGPT answer as to whether his ejaculate would cause any discomfort to the calf).

Case 6.—A man ejaculates onto the shell of a turtle he finds wandering by the creek, making sure—out of respect for its unknown goals and projects—not to disrupt its slow walk to wherever it might be headed.

C. Cases where the animal is the aggressor or enticer and both parties are sexually stimulated

Case 7.—An orangutan, branch shaking and chest-beating in showcase of sexual prowess, swoops onto the bathing primatologist, and she—excited by this, and feeling bonded to the creature she so often writes about and photographs—takes on a lordotic posture of access so he can take her with his diminutive penis, enjoying it afterwards when (out of curiosity, one would guess) he licks his own ooze from her vagina.

Case 8.—Having formed an attachment with a man who started swimming at the dock a year ago (so much of an attachment that she can recognize his car as she waits for him; so much of an attachment, in fact, that his human girlfriend is rightfully afraid to get in the water with him), a dolphin—in sexual forwardness complete with arousal whistles and belly-brushing passes of darting flirtation as well as vivid puckering and protrusion of her genital slit—starts to grind her double-A-sized clitoris against his knee and then (not high on pufferfish, mind you) mounts him when he sticks his penis out for her.

Case 9.—Getting the hint from the aggressive heat behavior of the family cat (the attention-seeking yowls, the restless rubbing on furniture and rolling on the floor, the increased affection coupled with rear-end elevation flaring out her vulva), the aroused boy holds up the eraser-end of a pencil, coaxed to do so by her nudging head, so she can grind away on it how she sees fit.

D. Cases where the human is the aggressor or enticer and both parties are sexually stimulated

Case 10.—A dog has been humping the throw pillows in sexual frustration for a week (heightening the horniness of everyone in the house, by the way), so the owner—out of both empathy and desire, but by means neither of coercion nor extra-sexual manipulations like treats—sucks it off to its intense enjoyment (jouissance evident not merely in its remaining in place despite its freedom to dissent at any point, but more so in its dopey smile and tail-wagging moans of release).

Case 11.—A man is feeling kinky and so, from his stool after a soothing groom session outside the barn, performs cunnilingus on the black mare who, to be clear, has not been specifically trained to tolerate this activity and who can walk away at any time and who exhibits various signs of excited receptivity: nickering vocalizations as well as tail lifting in a slight squat down to make the vulva more accessible—a position the man eventually takes full advantage of by slipping himself inside her while standing on the stool.

Case 12.—In a near future where scientists have synthesized dolphin pheromones, a dolphin-attracted aquarium director perfumes herself with the scent of female-dolphin heat and enters the after-hours tank, which results in one of many male dolphins—the one already bonded to the director—copulating with her (rather awkwardly, for whatever it is worth).

Cases 1-3 are unequivocally immoral, at least I will admit under the assumption that animals—unlike rocks and hammers—have inherent worth and should not be subject to suffering merely for our pleasure. Since in these cases the animals are clearly dissenting and being coerced while being subject to unnecessary pain and sometimes even death, the moral assessment here seems uncontroversial—yes, even if the hen’s traumatic death in Case 1 is a welcomed release from a life of confinement on the factory farm. Now, I will say—and perhaps this will shed some light on what I think factors in to deciding whether an incident of bestiality is morally permissible—that, with only a few tweaks, Case 2 becomes morally acceptable. Let us say that the collie is not starved and that the women never forces its snout into her desired cavity. Let us say that the woman merely places the peanut butter on the area she wants licked (her foot, her vagina, or whatever area gets her juices flowing) and splays herself out waiting. If the collie comes in (say, without being called) and licks the peanut butter off to its enjoyment, and is free to stop at any point and move on, and so forth, then the incident is benign. Treats in themselves present no problem. What is the relevant moral difference between, on the one hand, putting plastic wrap on your head and sticking peanut butter on it so that your dog will lick it while you clip its nails (a common practice on TikTok) and, on the other hand, slapping some peanut butter on your foot so the dog will lick it off (and thereby get you off)? If anything, the former is worse. For whereas in the former you are doing bodily damage to the dog (taking away its defenses and even exposing it to possible pain), in the latter you are providing harmless and autonomy-respecting sensory stimulation that brings mutual pleasure.

Cases 7-9 are clearly morally permissible. These cases, on top of being mutually enjoyable, are cruelty free and consensual and aligned with the wishes of each party. Indeed, the human in each case follows the self-ruling lead of the animal, neither treating the animal as a mere tool of gratification nor exploiting the animal (say, by filming the interaction so as to upload it on bestiality forums—a procedure the animal could never fathom). Cases 7 and 8 stand out as especially unproblematic. The animals in both cases, exercising their personal autonomy in pursuing sexual pleasure, are not only undomesticated higher-order mammals, but also more physically imposing than humans and operating in elements (jungle and water) where humans—at least those involved—are vulnerable and lack the power to do much of anything to stop from being hurt or killed. Case 7 goes even further. It shows the potential for meaningful interspecies relationships, where humans and animals can form deep bonds around mutually-enjoyable sexual interactions aligned with each party’s goals.

Cases 4-6 I also regard as morally permissible. Even though the animal in each case has no idea what is going on, no distress or coercion is involved and the animals are free to pursue their own agential goals without disruption. These cases are morally permissible, in short, for reasons similar to why it is morally permissible—so at least I assume—for the primatologist in Case 7 to take the orangutan’s photo (even though the orangutan has not even the slightest conception of photography or what taking a photo amounts to). Now, it could be argued that the man in Case 5 is using the calf as a mere means to his own satisfaction. To this I might respond how some slaughterers respond to the ethical objection that they treat cows as mere means to their own personal gain. Namely, just as the cows are not being treated as a mere means in being slaughtered since the cows were paid with food and shelter, the calf in question is not being treated as a mere means when the man lets its suck his penis since it is paid with food and shelter (and, so we can imagine, loving care until the end of its natural life). One might insist “But it wants to suck a milky udder, not a penis.” Although I remain unconvinced of the relevance of that fact, I can just change the example to avoid debate. Let us say it simply wants to suck on things for self-soothing reasons. Let us imagine that the man knows this and gives over the penis. He uses the calf in this case as a mere means no more than I use a dentist as a mere means when I have him fix my teeth for money. I am willing to drop the point, though. For clearly the humans in the other two cases are respecting the goals and purposes of the animals (and so do not reduce the animals to nothing but tools).

Cases 10-12 might seem more controversial since the human is the initiator. These too, nevertheless, I regard as morally defensible. All parties experience gratification without distress and all parties are able to dissent at any time. Nor is any animal being treated as a mere means. The human in each case does the equivalent of asking for permission—permission, when applicable, simply to touch the genital region (rather than doing what would be permissible anyway, at least according to the standards we use in instances of animal touching whose permissibility we would not think to question: namely, making a quick pass over the area to gauge the animal’s receptivity). The human in Case 11, for instance, procures the mare’s receptivity to genital touching before even the slightest contact with that area. To be sure, the woman in Case 12 uses a mate-attraction bait to enhance her desirability. But this is unproblematic throughout the animal kingdom: from courtship dances in the case of blue-footed boobies and peacock spiders, to pheromones and acrobatics in the case of bottlenose dolphins, to bioluminescent flashes in the case of fireflies, to perfume and makeup in the case of contemporary humans, to use of optical illusions for making one’s bower look bigger in the case of vogelkop bowerbirds, to rapidly changing color displays in the case of octopuses. For whatever relevance there might be in saying it (and I think there is none), the use of pheromones in Case 12—as with the use of all the other courtship manipulations just mentioned—does not necessitate copulation. Let us assume—as is true in the case of humans, where even the most beguiling cologne is insufficient to secure sex—that the prior bond was an additional factor for that dolphin, unlike the others in the aquarium, copulating with the director.

Notes

[i] Dekkers 1994, 149.

[ii] It is common to distinguish bestiality from zoophilia (see Miletski 2001). Whereas in bestiality the nonhuman animal (hereafter simply “animal”) is used as a mere prop for sexual gratification, in zoophilia the animal is treated as an independent agent worthy of respect (Haynes 2014, 127n31; Richard 2001; Maratea 2011, 926; Wilcox et al. 2005, 205:307; Rudy 2012, 606). In this paper, however, I use the term “bestiality” to refer to any sexual interaction between human and animal—fondling, teasing, penetrating, or any other contact of a “sexual nature” (whatever that exactly means)—whether caring and conscientious or cold and careless; whether born of some entrenched paraphilia or simply a matter of exploration or religious ritual.

[iii] See Haynes 2014, 124n14; Holoyda 2022; Grandin and Johnson 2005, 103.

[iv] See Beirne 2000, 314; Beirne 2002, 195; Ferreday 2003, 284; Adler and Adler 2006; Maratea 2011; Valcuende del Rio and Caceres-Feria 2020, section 4.

[v] See Wisch 2008; Haynes 2014, 123-124n13. Wisconsin’s broad statute makes it a crime even to “transmit obscene material depicting a person engaged in sexual contact with an animal” (see Holoyda 2022).

[vi] See Thomas 2011, 159.

[vii] Miletski 2005.

This essay is unpublished

Interesting AF

Thank you