The Tooth (Round 7)

Let's workshop this poem about how a son would prank his inebriated father, tormenting the man on physical and mental and emotional levels as a way to feel in control (in an out-of-control milieu).

scent of the day: Fleur Tabac, by Miyaz

First wear. I need much more time.

A deep industrial smell in the rubber-plastic direction but in a very specific tackle-box way: smells exactly like the those packages of scented bait, Powerbait, where these squishy-gooey-gummy plastic worms (some with ribbon-tail or curl-tail design and with embedded flecks that glint in sunlight) have been impregnated with a supercharged formula that smells a lot like the processed fish food they feed fish at hatcheries: pungent, oily, savory, fermented in a cheesy way that trout and catfish love—all this decaying marine protein smell, a meaty and brothy umami (like soy sauce blended with cat kibble and rancid butter and licorice spice), overtop chemically-potent industrial plastics (something betweemn boat epoxy and an inflated beach toy). /

this scent opens with a proteinic fervor of fermented fish meal, wet polymer, and sunlight-warmed dock wood. / It is confrontational, but oddly nostalgic: I get marine feels despite the otherwise early profile (althoygh perhaps some ambroxan is used) and I get memories of bait shops and summer mornings thick with the hum of insects. / I was expecting the assam to be shitty—if anything it is cheesy and fermented with earthy hints of worm body decay (the dapper worm of Figment Man now rotting). /

As the spicy volatile top fades, something deeper, more contemplative, emerges: a tobacco-like warmth, equal parts fermented leaf and boat resin. / The scent begins to whisper of pipe tobacco left in a tackle box—molasses-dark, slightly smoky, with a whisper of licorice, cedar sawdust, and greasy metal./ There’s a strange dignity to it, like a cologne for retired anglers who’ve smoked cherry blends for decades and still keep their waders by the door—indeed, people from a far get a cherry woody smell /

Hours later, what remains is as alluring as a fish lure: a plasticized amber glow. / The fishiness recedes into a dry, tarry, almost creosote sweetness—reminiscent of old humidor wood, oxidized oil, and the faint ozone of creek water on vinyl. / It’s as if the scent has aged into something both mechanical and organic, caught between industrial nostalgia and biological persistence—exactly like Powerbait /

It might seem strange that this is, first and foremost, a tobacco scent when it is so clearly creek-fishing-tackle-box Powerbait, but I do get tobacco from multiple directions even so—the main overlap being that the fermented proteins of the lure align with the fermented leaf of tobacco and that the oily plasticizers of the lure align with the resinous and smoky base of aged tobacco products). /

First, fishing has always been associated with tobacco for me because my dad, who took me fishing, chainsmoked the whole time. / So tobacco impressions might ride on the coattails of any scent that brings me to fishing memories—I believe Honour Man does that merely by bringing me to the sea./

Second, one of the defining characteristics of cured tobacco—especially Burley or Cavendish—is its fermented, proteinic sweetness: that faintly yeasty, haylike, molasses-and-ammonia mixture, which we get here and in actual PowerBait—both cured tobacco and Powerbait have a core of dark maltiness, the same family of smells that bridge barn-cured leaf, fermented grains, and animal feed. /

Third, PowerBait’s formula uses oily binders and plasticizers that lend a tar-like, resinous base note not unlike the smell of pipe tobacco jar resin or even old humidor glue and cedar—this resin-plastic mixture giving off a burnt-sweet, phenolic warmth that parallels the smell of freshly opened tobacco tins. /

Fourth, PowerBait often has an anise edge (black licorice or fennel) and that his right in line with how some pipe tobaccos are cased (and is what Zarokian emphasized in the still unbeatable masterpiece Royal Tobacco). /

Fifth, rancid nuttiness (like old walnut shells, molasses, or fermented honey)—tobacco leaf during fermentation and PowerBait both pass through that zone (a territory where castoreum, coumarin, and tonka bean notes sit). /

Sixth, the industrial plastic undertone—the “tackle box” smell—has surprising parallels to the burnt phenols and creosote found in dark-fired tobacco or cigar wrappers: the faint whiff of smoky solvent that rides under PowerBait’s scent can recall the chemical warmth of a freshly lit cigar or sweet tar on old briar pipes.

Worked on section 2 today.

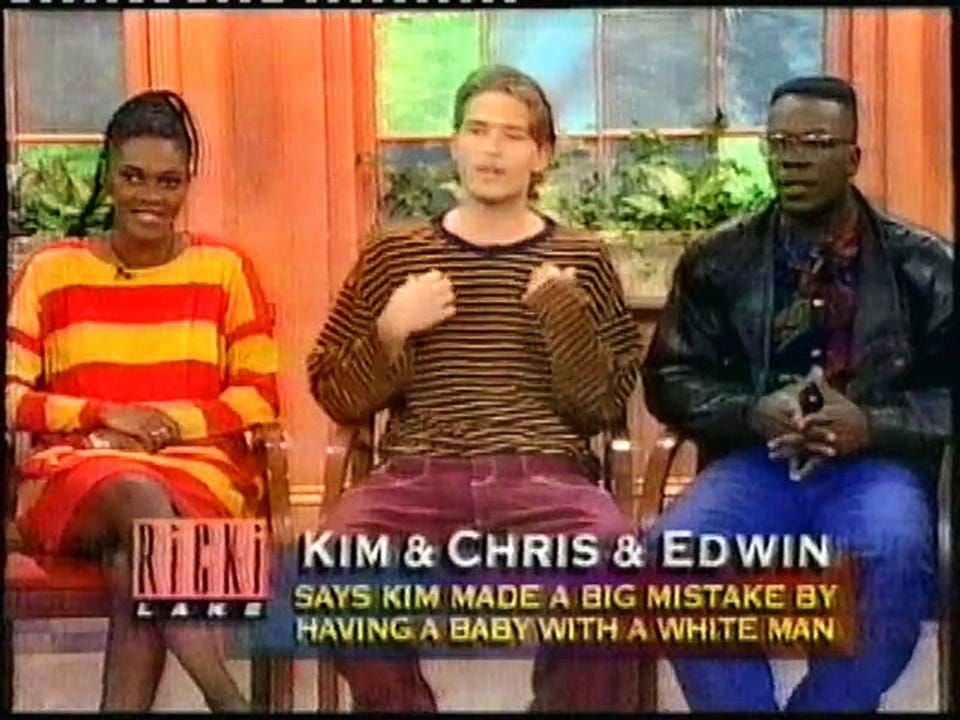

The Tooth 1 The snap-sizz of a match, the rasp-click of a Bic—amens like these were peanuts next to the crack-fizz of a can. Five-six and balding since twenty, he would torch up a Newport 100 from the bent stump of the last—blazing through them like my thumb with the rosary he held at his wake. “Daddy’s got a fixation—an oral fixation,” he would grin at my coughs (contract via confession). But the beer bothered me most. “Daddy’s got a thirst.” My nagging tears futile, his swear-on-me promises to quit the guzzle broken too many times, a distracting thirst to fuck with my father (fierce, all my own) flowered under moonlight—just like that older thirst for Pepsi to wash down the Doritos, the Slim Jims, the Ring Dings in my transfixion before junk TV. Eyeing him for years at our kitchen-living-bedroom table, all waking hours smashed by his go-to Busch Light, could you blame me? Frisbeeing bologna, liverwurst, on his head as he snored adenoidal arpeggios in cruel oblivion on the hardwood (fist-pump bullseyes landing in minuscule splats); piling board games and phone books on his chest, his face, (cans, lit candles, cologne undulant in Jenga precarity); pinching his nose, his mouth, to silence the apneic rattle, flappy snorts and gasps that eclipsed (as if on purpose) my shouts: “Dad! Yo Dad! Go to the damn couch!” I was hooked on such sweet-caffeinated sips of prankery before tolerance set in. And I snared others into the web. My friend and I once sharpied a clown face on him— black angles sharp around the mouth and eyes like Gacy, which in the noon sun (nickels still stuck to his bare gut after his piss) I said he had drawn himself to amuse us but later, our accounting for burns turned sores, had us scrub with the green part (the only part) of the sponge. 2 Films on Lifetime, binkies after Ricki Lake at five—my dad liked their drama while he calibrated himself for the floor. Their “Mommy loved me too little, Daddy too much” only honing the mental slant of my mischief, in ambush I would wait for that soft spot just before gravity won out. And when it came my intonation would twist histrionic, shaking like an after-school special: “Reefer?! Who, Son— who taught you this?” “You, alright!? I learned it from you!” Anthropologist of dysfunction, weaponizer of emotion— I would take on a posture of too-sad-to-snack dejection and, at an ad break, go something like: “Hey Dad, can I—? Never mind. It’s fine.” Eyes up at the nicotined stalactites as if fighting back tears, this would suffice to draw him in. “S’matter, Boy? Tell Daddy.” “I’m havin,” voice cracking, “well, problems—problems back home, at Mommy’s.— I, I don’t know. It’s fine. You wouldn’t understand.” “Huh?” He would have me mute the TV, brow furrowed to match my drama; mouth slack, beady eyes befuddled, concentration quivery versus inebriation’s tug: “The fuck” (said slowly) “you talkin, Boy?” Hands over my face, both to hide chuckles and to hint how deep this goes, the scene would unfold like a liturgy: “Well, he—.” “He!? He who!?” “Can we just watch the movie?” “Tell me the fuck now!” “After—I don’t know. After, he says—never to tell or—.” “After!? After fuckin what? This fuckin’ for real, boy? Don’t tell me no lies.” “I’m not allowed to tell. Okay!? He says, if I tell, ‘it’ll break, it’ll break—our little secret.” “Our little fuckin secret!? The fuck!? Don’t bullshit me!” “He says it’s, it’s just for us. I can’t even tell Mommy.” “Mahfucka. Say what the fuck’s going on, Son. Mikey!” “I’m tellin lies. Forget it!” I would yell, wiping fake tears (aikidoing chuckles into sniffles). “Just forget it, Dad.” I would clam up at this point. He would go from sobbing to smashing his beer-can castle (“Touch my son! Watch! I’ll kill that motherfucker!”), back to sobbing, then soon to dream mutters of rage despite a Newport cooking his insensate pointer (forever hooked rigid by a steel pin after a tendon tear). “It’s just—” I would say, prodding his gut to pull him back from snore land, “it doesn’t feel good. Dad, I don’t want to play any more ‘love games.’” 3 One weekend night, my father sat groaning about his tooth. “Gonna yank this bitch!” he repeated. “You can’t do that,” I insisted, his repetitions finally having broken through my concentration on my own consumptions. Tone roused again to after-school hyperbole, “Dad,” I baited, “you need a dentist for that.” “Shiiit! Daddy don’t need no dentist, Boy.” “Pull your own tooth? Without medicine?” Beer held high, “Pop’s medicine,” he said and sang his version of Domino’s “Sweet Potato Pie”: “I’m all fucked up and I don’t know why. Feeling kinda freaky, that’s no lie.” “No way,” I cut in. “Daddy don’t lie to his son.” A junky at ten, toying with prey (like bored housecats) was a natural response to the weakening highs. So instead of jumping right to “Prove it, then,” I fell into brooding silence, until just before uvular flapping. “I know it all,” I said, decibel for outdoors. “Stop faking. Mom told me.” His grimace again one of wobbly perplexity, “Fakin’? What shit your mom been talkin’?” “It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t change things.” “You idiot. Make no goddamn sense, Boy.” “I know. Okay!? You’re not my dad.” Cheeks risen, squinting out sight and baring top teeth, “What!?” he said. “Tired of these goddamn mind games.” But having had soaked in tales he would never have thought he had told me— banging wives of impotent men for pay or, key here, fresh from the Corps saving my soon mom from Chris, a biker boyfriend—I had an angle. “She told me everything. She took me to see my real dad. He’s okay, I guess. It’s more fun with you, th—.” “Who the fuck we talkin’ ’bout?” “He told me I don’t have to call him ‘Dad’ yet. I can just call him ‘Chris’ for now, or just ‘Mr., Mr. Condon.’ He took me on his motorcycle!” “Watch what you say, cause I’ll kill the bitch. Shiiit. Look at you, Boy. You Istvan clan!” “I don’t want you hurting yourself if you’re not my dad,” I said to get us back on track. His face scrunched. “What you talkin’?” “If you’re not my dad you don’t have to prove anything by, by pulling your tooth.” “I am your dad! If I love ya.” He raised the hook forever fused to that phrase. “And ain’t got shit to prove. Bitch’ll get yanked real quick, Boy!” “You sure you’re my dad— enough to pull your tooth!?” “You don’t know shiiit. Get those fuckers.” His chin flicked up to the linesman pliers on the TV. Blue-handles grease-stained (since I was the channel turner), he raised them as if at the end of a toast, “If I’m your father,” and went right to wriggling work, wrenching the molar out, long roots barnacled. Linoleum splattered red, “If I love ya!” he said.