Letter of Grievance (redacted) (ROUND 2)

Let's workshop this letter that helped my reinstatement to my academic position after the heights of the recent safe-space hysteria saw me fired by white fuckers without due process for off-duty art

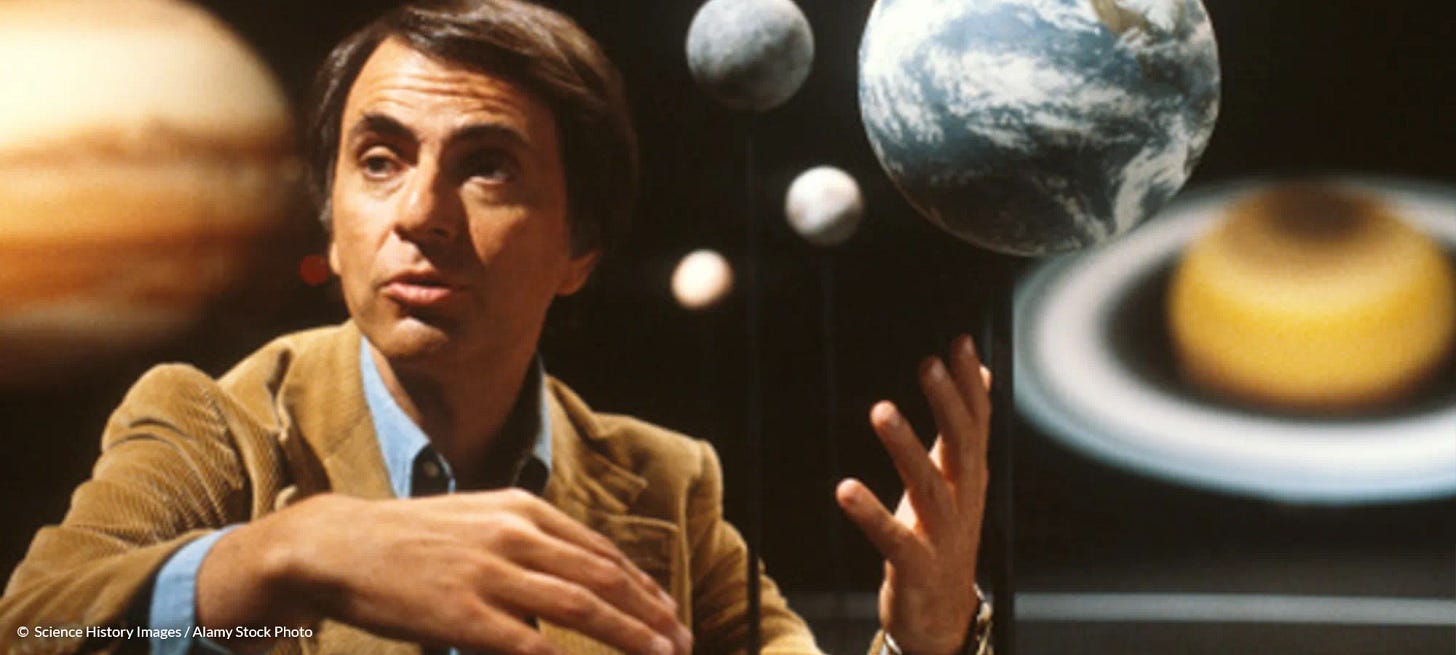

Whatever the problem, the quick fix is to shave a little freedom off the Bill of Rights. Yes, in 1942, Japanese-Americans were protected by the Bill of Rights, but we locked them up anyway—after all, there was a war on. The pre-texts change from year to year, but the result remains the same: concentrating more power in fewer hands and suppressing diversity of opinion—even though experience plainly shows the dangers of such a course of action.—Carl Sagan

MOST

YOUNGKINGS GET THEIR HEAD CUT OFF—Basquiat

Hello HR team and Executive Vice President, Vice President, and AVP

I appreciate getting the chance to appeal my recent termination. My lawyer, XX XXXXXX, thinks it likely that XXX has encroached upon several of my constitutional rights. For reasons I lay out in this note, his opinion does not seem farfetched. That the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education has so readily jumped on my case, covering all legal expenses as well as offering diverse forms of support, is an additional telling sign. If my training in the humanities has taught me one thing, however, it is intellectual humility. I leave the technical legalese and the interpretation of the Constitution to the experts, never forgetting all the while that even experts might disagree. Nevertheless, my note here, which I attach to my completed statement of grievance, should establish at least that the termination was excessive and that the termination process was mishandled.

The dean of my college (Liberal Arts) emailed in March to inform me that, as a result of an investigation into my artistic activities (and specifically how they were incorporated into my role as educator), I would no longer be allowed to teach at XXX. The Dean said that, aside from having a public presence unbecoming for anyone calling themselves “a teacher,” I had been found in violation of XXX's AR 3.05.002. The technical point was that, in using official email to point students to my YouTube page, I increased the odds of their viewing potentially “racist, sexist, threatening, sexually explicit, obscene or otherwise objectionable material,” which at XXX is “strictly prohibited.” Through the discussions between my lawyer and the lawyer representing XXX, the specific reason for my termination came out months later: a few students, exploring areas of YouTube beyond the intended course lectures, stumbled upon what they should never stumble upon in any spaces linked to XXX classrooms: “objectionable material.”

I was surprised to receive the email. I was surprised, yes, by the extremeness of the judgment against me (termination issued with a tone of finality)—an extremeness magnified when set against (1) the support I have received from colleagues (XXXXX XXXXX, XXXXXX XXXXXX, XXXXXX XXXX, and XXXXX XXXXXXX, most of all) and (2) the praise I have received from students (top ratings, and nominations for XXX’s Excellence in Teaching Award almost every year). But I was just as surprised—enough, in fact, to think at first that the dean’s email was spam—by the out-of-nowhere nature of the judgment. I received no notice of complaints about my YouTube page. Worse, I received no notice that an investigation was underway in the first place!

Even if due process is not a top priority for more disposable faculty (such as myself), it is still alarming (1) that the very email notifying me of the investigation states the findings of that investigation and (2) that the standard procedures prior to termination were bypassed: written warning followed, if need be, by trainings or even a period of probation. Just consider the wildness of it. The subject line of the email notifying me of my termination was “notification of investigation”—yes, of investigation! To make matters worse, I was not offered a chance to remedy any issues (whether through offering an apology, undergoing training in “right think,” taking a speech-restrictive pledge, clarifying the intentions of my art, or even—disquieting as it would be for me to have to do—censoring my art). I deserved more fairness than XXX extended.

My lawyer—who stresses that, as a public institution, XXX is compelled to extend due process to its employees—has faith that the Constitution can protect artists and academics from rights violations. I am much more cynical. Tarnished as it already was in my eyes (after close inspection in my undergrad years revealed that its stars were in truth corporate logos), the American flag looks different to me now. I have witnessed, especially over the last five years, widespread censorship of artistic and academic expression with little concern for due process. Just think about it. A professor was replaced for teaching the Chinese word for “um” since it sounded perilously close to the n-word. The examples keep mounting. And that is perhaps why the first lawyers I reached out to (before contacting The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education) all gave me the same pessimistic message: “Protecting free speech and due process is no longer a priority in this climate and so, unless you have a lot of money, you have no legs to stand on: you are a mere at-will adjunct, and in Texas of all places.”

So for the sake of the argument (and in opposition to the inspirational idealism of my lawyer), I will grant that I am not entitled to as much due process as fulltime faculty. That said, I should be afforded at least a bare minimum. It is not simply a matter of common courtesy, or even the Constitution. XXX’s own rules, as well as various statements from the Office of Human Resources, confirm that employees—mere adjuncts too—have due-process rights: “XXX makes every effort to provide employees the opportunity to improve their performance in accordance with XXX policy before considering termination of employment” (see termination guidelines as well as AR 6.08.003). XXX did not make every effort to do so in my case. XXX made no effort. Indeed, I reached out to several people to initiate an appeal, which XXX also admits is a right (even of a mere adjunct), but was ignored (as I was, by the way, by colleagues in my own department—and even when I reached out to them for official matters related merely to finishing out my Spring duties)! That the decision against me was so severe (and unjustifiably so, as I say more about below), and that it appears to have been reached unilaterally (which seems at odds with XXX’s administrative rules), only heightens my concern with the lack of baseline due process here.

Look at it this way. It is bad enough when a professor is forced to use course materials and modes of speech that conform to some sanctioned ideology. It is bad enough when a professor is forced to undergo “trainings” to ensure that his perspective is in alignment (Ausrichtung) with what is righteous and pure, no longer “problematic” or “unbecoming.” And yet in my case, XXX jumped straight past attempts to assimilate the outsider and right to the residential-school-burial-ground of removal (Abbeförderung), bypassing these arguably tamer violations of “freedom of conscience.” Given the growing trend of professors censoring themselves even at the expense of dulling down classroom discussions and holding back the bedrock principles in their field (such as that, yes, we share a common ancestor with chimps), given the growing trend of professors redacting past expressions that might have offended people (as in when the endocrinology professor takes back any suggestion in the last lecture that he might have endorsed the notion that biological sex is not a construct), why assume that I would not conform? As it turns out, I would not have conformed. But did you know that for sure? None of you are acquainted with me one bit! With time now to reflect from hopefully a more dispassionate point of view, it should be clear how radical the decision was.

I implore whoever might be reading this to empathize. I myself, for whatever it might be worth, have tried to appreciate the various factors motivating the administration’s position. For the same reason publishing houses and film studios must “play it safe” (trimming away as much unorthodoxy—true unorthodoxy—as they can) if they want to achieve the most profit (or at least avoid being canceled), the administration’s hands are tied: cancel culture is largely a student movement and the students, at least according to the business model that has swallowed academia, are the customers—and who, who I ask, is always right? As a provocateur and an iconoclast, that means I am potentially messing with people’s money. I am not naïve to that. No wonder all it took for swift eradication, then, was that a few students “stumbled upon” content they found unsettling.

Nor am I naïve to the fact that there are codes of etiquette at least implicit in academia, and that more and more—now that making sure that no one is made uncomfortable is becoming top priority—officials are cracking down on their enforcement. Just as it is considered bad manners (at least according to mainstream yachting communities) to give a fine yacht a jarring name such as “ShaNiqua” (see Rigg’s Handbook of Nautical Etiquette), it is considered bad manners (at least according to mainstream academic communities) to appear in a way unbecoming for a teacher. I might have given as an example here pierced and tattooed. I might have (1) had it not become now a trend for professors to look to take on, with some purple hair and mockery of white people mixed in, this look as a signal of solidarity with marginalized communities (a sort of fake-safe-Disney iconoclasm, a fashionable radicality). I might have (2) had not the firing dean demanding I present myself in a manner more becoming of a teacher been covered with tattoos and piercings himself—or, to honor recent changes, themself.

Nor am I naïve to the fact that protection of free speech and artistic freedom and due process now comes—weird as it is to say, and as much as it shakes my identity to admit—more so perhaps from the right wing of the political spectrum, a wing with which—after the horror-show presidency over the last four years, with its brazen defiance of Enlightenment norms of accountable speech—few people in academia, let alone in the humanities, want to be associated. The point is reinforced by the regrettable fact that today it is considered, even in academia, a serious argument to say “x is wrong, or at least likely wrong, since it is associated with a group I hate.” So this is largely a political issue. And no wonder. Every thing is politicized—most recently and absurdly in the case of Simone Biles, even the mental health of athletes. Like it or not, we now regard one another, even in the most intimate spaces (at the thanksgiving table and in the bedroom), primarily as representatives of political identities. My victimization, then, is largely just collateral damage from this reckless and sad political battle (this Weltanschauungskrieg)—sad especially when seen for what it is: a cry-for-help tantrum testifying to how far we have let ourselves, our intellectual and parental and environmental consciences, slip. My victimization, to be more direct, is largely the result of people on one side of the battle hankering to earn their stripes, to show how down they are, to virtue signal—to virtue signal, yes, while at the same time, and precisely by stooping to rights-violating levels of vindictiveness to do so, to justify (to themselves and to the world), through a warped appeal to desperate-times-call-for-desperate-measures logic (Daseinskampf-style), the righteousness of their battle efforts in the first place!

Dramatic as this all sounds, it is a human story. With exception to the rare monsters of unfeeling, one cannot sleep as a middle-passage slaver without the blankie of a consoling yarn. Yes, I am human. I too spin yarns. It is crucial, then, to return to colder facts.

Flagrant disregard for due process would be called for, so at least I will grant for the sake of the argument, in extreme cases where there is immediate cause to act. Fine. But that is not the case here. Nowhere did I direct students, or any other XXX community member, to specific videos beyond my academic lectures, let alone to videos that violated AR 3.05.002. The facts are plain. Two YouTube links were provided: one to my academic lectures and the other to my page in general. To find anything that might be reasonably regarded as “off-color,” one would have to hunt through my videos themselves (of which there are about 100). No fair-minded person would say it is wrong, or even in bad taste, to link students to YouTube in general (youtube.com), where after enough hunting they no doubt could find something upsetting: a yacht named ShaNiqua, for instance. How is my case different, substantially different?

Every video, moreover, is age-restricted to the highest level and contains a content forecast preparing viewers for anything controversial. YouTube, besides, gives each viewer the option of viewing from a “Restricted Mode” where only the most Disneyfied videos are accessible. YouTube forbids any sexually-explicit content, in fact. Its sophisticated software did not flag any of my videos, even the one video that threatens to spill over into erotica, because I made a concerted effort—using fake props, cut outs, photoshopped polaroids, and blur effects on top of quick and covered passes across the screen—to keep within range of YouTube guidelines.

Can you appreciate, in light of all this, how hard it is for me not to sense the machinations of bitterness, or perhaps of some other unstated reactive emotion, behind these motions against me? While I suspect that administrative forces—businessmen, ideologues (I do not know)—are operative behind the scenes in this regard, I know where the machinations began. In one of my course sections, a dogpiling movement began on GroupMe to try to get me fired. The motivation for the movement is clear: payback for my open resistance to cancel culture, payback stoked by the “Oh yeah, well we’ll show you then” mode of being characteristic of entitled youth atrophied in their empathy skills, groomed to categorize all reality in terms of red and blue, and desperate for a sense of power and importance in an anti-intellectual country hopelessly dysfunctional in its melodramatic pendulum swings of overcompensation (years of toxic messages like “feelings are weak” and “show some balls” and “no one owes you shit” and “its not about you” only to be replaced, for example, by years of equally toxic messages like “feelings are all-important guides to true reality (even in the hard sciences)” and “anything unsettling is a trauma worthy of revenge” and “the world owes you everything (comfort, safety, über alles)” and “its all about you-you-you”). Which course section it was is also rather clear. At all the institutions at which I have taught, I have received top student ratings—except for one class at XXX last Spring.

As powerful as these points may be, they are insignificant compared to the definitive point. That I was allowed to finish the Spring semester indicates that XXX itself did not think there was immediate cause to act. That XXX itself did not think there was immediate cause to act shows, in the end, that the flagrant disregard for due process was uncalled for (even if we bracket my earlier points). It was uncalled for according to XXX’s own standards!

My lawyer has indicated how XXX would respond to such a line of reasoning. “Actually, we at XXX did think there was immediate cause to act. We got you to stop linking students to YouTube. That was the immediate emergency.” Were XXX to commit itself to such a response, it should be clear what my own response would be. “Why would not merely stopping me from linking students to YouTube, why would not that alone (and perhaps with a little HR indoctrination sprinkled in), have sufficed for a disciplinary measure?” That termination was the go-to response is not only alarming but, again, suggestive of something else going on here. And that this is all set during the height of the pandemic only underscores the point. We in the humanities know, perhaps better than anyone, the need to be more caring, charitable, and patient in times of crisis.

What exactly, one might wonder, was the objectionable content on YouTube? My lawyer has informed me, after having discussed the case with XXX, that two of my invented characters—Mrs. Tong and Mr. Slow Man—were the specific problems. Given the due-process issues laid out above, my case need not rest on any explanation of my artistic content. And even independent of the due-process considerations, no burden falls on me to explain the intent behind these characters. After all, even if their main point was to cause offense, which is not the case (for reasons I explain below), terminating me for having created them is like terminating an author from his post-office job because his book contains a tattooed serial killer. I do not think anyone should be fired for their art, and by no means for their off-duty art! But it is especially jarring—as jarring as that Republicans, the party I always associated with censorship of art, is now the party that protects against the censorship of art—to witness institutions of higher education, the last bastions of free exchange of ideas, be so committed to shutting down viewpoint diversity that they will terminate employees merely for characters appearing in their artworks! Ideology-driven censorship should never rule the college campus.[1]

And yet what am I really to expect in such times of medded-out and sheltered children growing in a culture that incentivizes them to see themselves as traumatized and victimized (the more the better), times so reactionary that—I kid you not—more and more literary magazines, another (former) home for free expression, ban and even dox authors who submit stories or poems where a character from a marginalized community gets injured in some way? Things have gone bonkers. Have we forgot Sakharov’s warning over fifty years ago: “Freedom of thought is the only guarantee against an infection of peoples by the mass myths, which, in the hands of treacherous hypocrites and demogogues, can be transformed into bloody dictatorships.” Academia is not immune: censoring uncomfortable reading materials, forcing apologies from those who have voiced unorthodox opinions, and so on. A good case can be made, in fact, that academia is, in a sense, the very radix of such lunacy!

In the spirit of being accommodating, which I have always tried to be, I will say a few words as to the point of my characters. In general, I tend to use them to satirize our culture. Satire is an effective maneuver, common among the great writers in the humanities tradition, to push people to become more self-aware. Mr. Slow Man is an instantiation of a naïve-narrator literary device, a device commonly used for purposes of satire. (Think of Ricky Gervais’ character Derek, for a similar example. Think of Candide or of Holden Caulfield. Think of young Huck Finn shocked to find that Jim, a runaway slave with whom he travels along the Mississippi River, can miss his family as much as whites can.[2] Think of how Huck—before ultimately resolving to commit to a path that his conscience tells him to be blasphemous—tends to feels sick to his stomach, and to the point of wishing he were dead, whenever he reflects on the fact that, in helping Jim along his plight to a free state, he is complicit in violating one of God’s chief commands: never steal another person’s property.[3]) The innocent perspective of Mr. Slow Man, a gullible and good-hearted and honest character who does not understand the events surrounding his life as would a “normal” adult with “normal” values and a “normal” upbringing, welcomes—indeed, calls us to tarry within—an atmosphere of ironic observation. Mr. Slow Man, you see, allows me to question mainstream patterns of behavior and highlight cultural sore spots in the same oblique and humorous and disarming way we see in Twain, yet another artist—misunderstood so grossly it would have to be on purpose (lest we admit that we Americans are even dumber than the rest of the world sees us—who is now being retroactively censored. Especially for nonacademic audiences, that approach can be more impactful than the direct and unironic approaches I take in my capacity as a researcher. For all the flat-Earth-reminiscent rationalizations he provides, Mr. Slow Man shows his misguided gullibility in thinking, for example, that aliens have invaded. And you know what? Shaking their heads at him for his (cute) silliness (and getting a hit of dopamine through the reminder, thereby, of knowing better than him), that might provoke some among the growing number of believers in unhinged conspiracy theories to appreciate their own possible (cute) silliness, which perhaps they would not have otherwise (that is, had I confronted them directly and gravely and paternalistically—confronted them, in effect, in a way prone to incite defensiveness—with “You are wrong and here is the step-by-step proof why”).

It is just a trick, really—an old trick. A writer can achieve authority by having a character or a narrator get things wrong: wrong dates, wrong events, misinterpretations of other characters or of world events. People like to be right. And so if a narrator says something false or stupid, it evokes in the reader an empowering rush of pity. The reader feels smart and alive and dominant. (And that is why, by the way, when people do not feel you have given them a gift in saying something heretical, that is a sign that they think you might be right!) It should be clear how this works. Even a reader at Twain’s time who thought that chattel slavery was a good institution is now pulled by Twain’s manipulative machination to find their hearts insisting: “Of course blacks get homesick as much as whites” and even “No, Huck. You’re not violating God by supporting a runaway slave.” Like rape orgasms, few of even the worst monsters of racism can stop these sorts of statements from bursting forth from within them.

Satire and hyperbole are common tools of critique. Unless our tribalistic dystopia is much worse than I imagine, no professor associated with the methods of the humanities could fail to see this. That is why I am reluctant, as my statement-of-grievance form makes clear, to name any particular person against which I am raising a grievance. I sense, as I suggested in my response to the termination email, that impersonal pressures are at work here (perhaps ultimately pressures to pander to a consumer base), pressures driving out-of-touch higherups to issue orders to middlemen who then are to see those orders through (even against their own better judgment). When it comes to the figures I could name, I sense that orders are being followed with an attitude of resignation (Befehl-ist-Befehl-style). Horrible as that itself would be given what has historically followed in wake of the slogan “Befehl ist Befehl,” it is even more horrible to imagine that any of the figures I could name—all of whom are in-touch with the ruth-nourishing and ideologue-repelling nature of the humanities—could ever be the source of the orders for my Abbeförderung. (Of course, I could be wrong about it all being impersonal. It could very well be, as certain colleagues have sworn in confidence to be the case, that my excellence in both teaching and publishing made the Dean insecure enough to lie in wait, even if it was over years, for a convenient excuse to fire me. Even if this is not true, I will be much more careful in the future about outshining higher ups.)

Let us look at Mrs. Tong in more detail, just to make this all more concrete. The point of the Tong video is to dismantle the monolith of black hypersexuality (through the backdoor-guerrilla means of satire). The main role of black women, so at least goes the entrenched and reinforced caricature, is to serve as primal sex object. No wonder, then, that one of the main ways for black female musicians to inveigle themselves into the good graces of our society (so that they can sell sell sell) is to act out this cultural fantasy. My Tong video was a response to the song “WAP,” where Cardi B and Meagan the Stallion—or, perhaps more accurately (and to extend to these artists the fairness that should have been extended to me), the whore characters they are playing—celebrate having their various canals “beaten up” so roughly that the men doing the beating are urged (yes, by the beaten themselves) to risk catching assault charges. Seeing so many young people so uncritically celebrate this song, my goal was to shine a light on how it perpetuates an unfortunate stereotype. More specifically, my goal was to provoke self-reflection, particularly the self-reflection of those who just eat this song up and yet who claim, at the very same time, to stand firm against the hypersexualization of black bodies. (Insert “hmm” emoji.) Those from the population in question I knew would be jarred to see Chinese women, themselves targets historically of the hypersexuality stereotype, trying to compete with black women as to who is, in effect, the bigger—more lubed and ready—tool for sexual pleasure. In having Tong say—and here we have again another instantiation of the naïve-narrator literary device—“Chinese women have most wet ass pussy (even more than Stallion B),” the hope was to make my target audience see their potential cognitive dissonance on this matter.

Do not get me wrong. First, I am a sex-positive feminist who supports liberated female sexuality and sex work as real work. Second, and as a shocking artist myself, I will never interfere in the free expression of shocking artists—yes, even if their lyrics glorify being a whore and welcoming bedroom treatment so rough that the men “catch a charge.” However, it is crucial that diversity be depicted. It is crucial that young people of all stripes do not grow up thinking what for so long our national culture—through much more than just the spread-eagle Lil’ Kim posters (in my own teen room)—has hypnotized them into thinking: that the main role of black women is to function as twerkbots of gratification, not as feeling and thinking citizens with assets beyond ass. I want to see more variety with women in hip hop. Standing up for true diversity, which is more and more a main mission in my life (and factors largely into the issue of my termination), is the purpose behind the Tong video. (Defending diversity is so important to me, in fact, that were we in a society where the stereotype was completely flipped—a society, in effect, that regarded black women as asexual creatures who loathe anything having to do with sex—you better believe that my artistic efforts would be devoted to exposing the ridiculousness of that as well, shattering the monolith!)

Now, I do understand that, in a previous semester, a student complained that my “trigger warning” was worded insensitively. My intention was not to hurt anyone’s feelings. In addition to pointing out that my class would mention safety-threatening issues like abortion and rape and homosexuality, my intention was to alert students to what I worried—and still do (now more than ever!)—to be an assault on educational standards and intellectual diversity carried out in the warm-fuzzy name of ensuring that no one is unsettled in the classroom. I took steps to change the language of my trigger warning in later semesters to make my intentions clearer, even inserting offense-effacing asterisks when spelling out troublesome words like “holocaust” (“holoc*ust”). Indeed, and taking into consideration that the word “trigger” itself is triggering to some students (being that it evokes images of guns), I have plans to start calling my trigger warnings either “safecasts” or “bravecasts” or “content forecasts.” Adjusting my content and methods in light of external feedback does testify to my compassion and amenability, which only further drives home the due-process concern with jumping straight to termination.

An administrator at XXX insists, so my lawyer tells me, that my due process was respected in that I was made aware of the complaint about my trigger warning. That makes no sense, even on my arguably too-low standard of due process. My termination concerned directing students to YouTube. That has nothing to do with the light reminder I received from the chair of my department, XXXXX XXXXX, to be more careful with my trigger warning—more careful, in effect, not to alienate students in the very warning meant to make them feel welcome (a wise point). The two issues are unrelated. And even if by some magic of quantum entanglement they were related, no effort was made to show the relation in the termination email.

Still, the primary point is this. While students have a right to make complaints, I should have—even though I am just one of countless adjuncts, mere Lebensunwertes Leben in comparison to the customers—at least minimal protection under the First Amendment to express viewpoints disagreeable to some. College campuses invite, or at least should invite, competing viewpoints. College is a place where students go, or at least should go, precisely to be unsettled! Any institution that respects academic freedom and free speech, which XXX at least says it does (see XXX A.R. 6.02.002), surely should not penalize—or, as in this case, abruptly terminate—faculty members for presenting marginalized viewpoints in class, let alone for their off-duty artistic speech. We set ourselves on a path to our own ruin, first the ruin of our intellectual life, when we attempt to ruin—fire, dox, deplatform, hound out of public spaces—figures whose points of view conflict with the growing number of taboos erected each day, or when we attempt to ban uncomfortable discussion, for the sake of safety über alles.

I do hope that my philosophical outlook, primarily concerning my opposition to what I see as an anti-education movement of anti-intellectual thugs to strip classrooms of unsettling content, played no part in the decision against me. But given how excessive the decision was, as well as how much I have been ignored at XXX (even by outside departments) in the wake of that decision, there are legitimate concerns. To be sure, I do not write academic articles or poetry or satirical textbooks or comic routines or so on in ignorance of the growing threat to artistic freedom. I am aware that, worldwide (and in the US perhaps above all), artists are censored and intimidated—sometimes by their own families and even by themselves—more and more under the feel-good banner of protecting the youth from corruption and protecting the perhaps soon-to-be most fundamental of American rights: the right not to be offended—a . In fact, one of the larger motivations behind my art is to push back against the bloodthirsty saturnalia of censoring, silencing, and shaming that has swept over the well-to-do West. One of my larger motivations, put positively, is to keep the circumference of what can be expressed wide enough not only so that our conversations stimulate critical and creative thinking, but also so that we have no fear of losing our livelihoods for expressing our humanity.

Far from corrupting the youth, I work, in effect, to ensure that the youth grow in a vibrant culture of diverse voices, a culture of inquiry in which termination is not a necessary consequence of heterodoxy—and especially not of today’s heterodoxy: resilience, rationality, respect for evidence over opinion, courteousness toward those with different perspectives, defense of due process and free expression, recognition that growth (wisdom, empathy, humility, strength) can come from being made uncomfortable, resistance to the urge to rage at the world anytime it does not cater to you, refusal to see all disagreement as traumatic, opposition to the warped definitions of dog-whistle terms in the culture wars (especially “problematic,” “phobic,” “accountability,” “trauma,” “diversity”), aversion to letting your tribe do the thinking for you, and so on). But while by no means did I—a stranger, a weird-swimming fish—think I was invulnerable to the anti-diversity tide of cancellation (especially since my sustained criticisms of that tide in my scholarly and creative productions no doubt invite retribution), I did not expect sudden termination from an institution that outwardly insists upon the importance of a humanities education. It is a humanities education, after all, that never lets us forget the hygienic role strangers play (unlocking sides of us we never knew, making us more self-aware, increasing our dexterity, ensuring that we do not reach British-bulldog levels of decadence through inbreeding). It is a humanities education, after all, that equips us to flag that Machiavellian move, repeated throughout history, of excusing inhumanity in the name of safety. So even if the swift decision against me did not raise so many concerns about violation of constitutional rights and contractual obligations, I would have been surprised.

Please accept this note, in the very least, as an invitation to discuss these issues. My primary hope is to ensure that other faculty members cannot be so easily terminated for their artistic works. I hope, in particular, that administrators and faculty can work together to remedy the problems with XXX’s rules and enforcement against free expression and due process. It would be best, I feel, to get third-party organizations involved, organizations such as the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education or the Heterodox Academy, so that XXX does not merely take the all-too-enticing easy way out: shifting from the practice of immediate termination of “problematic” voices (as in the case at hand) to the arguably-better-but-still-questionable practice of mandating that such Abschaum voices be “cured” through training in some approved way of thinking. My secondary hope is that XXX reconsiders the decision against me. I have enjoyed fruitful experiences with thousands of XXX students. I would love the opportunity to keep up my teaching role, which ultimately boils down to cultivating ethical and critical citizens who are willing and able to appreciate each other’s perspectives (as opposed to “cancelling” them).

In typical cases of conflict between employees and employers (even ones where fundamental rights seem to have been violated), I would conclude by saying that there is no reason why all parties involved cannot keep building a professional relationship. But with the growing kangaroo-court ethos of eliminating any entities—even comedians, artists, and professors—merely accused of being sources of discomfort or perpetrators of unsanctioned attitudes, and with the apparent order from on high to cease and desist from interacting with me, and with the due-process-less severity of the apparently unilateral decision against me, it is hard not to feel that my call merely to work together will be in vain.

I do hold out at least some hope, little power as I possess. Otherwise why bother with this note? Standing up for myself amounts to spraying the soil on which I travel, and on which others travel, with weed killer. Standing up for myself helps protect others from what lurks in every bureaucracy: spiteful authoritarians aiming to express whatever bit of power they can by issuing orders to crush any resisters of their policies and decisions or anyone subordinate who outshines them (as, again, certain colleagues swear in confidence to be true in my case). My resistance—my saying “No, this ain’t gonna fly”—helps limit their corruption, which would otherwise spread to any soil unsaturated with weed killer. But even in the worst case, which is that the weeds are immune to (or perhaps even enhanced by) my solution, good things have come from all of this.

First, and to speak more abstractly, the trauma of dealing with my termination, coupled with the call to articulate a defense for myself, further refined in my mind why it is so important to value free expression and due process. Because of this challenge, which has severely disrupted my life, my understanding of the importance of free speech and due process has become much more concrete—visceral, it is safe to say (as I write this in my new home: my hot car). The horrors I went through, rather than silencing my opposition to the assault on diversity of expression and viewpoint, have made me more committed to the cause. For that I am thankful. It is easy to think one is being an ally to young people, especially those from “vulnerable communities,” by sheltering them from jarring factoids or discussions or words. The truth is quite the contrary, and jarringly so when we are talking about youth at the college level. Administrators who insist upon such infantilizing practices reveal themselves to be the neo-oppressors of those they say they are protecting—poison in the guise of medicine. I understand that much better now. Enhanced understanding, of myself and the world, in some form or other is what I expected, of course. Traumatic experiences and antagonism and things failing to go our way serve as learning experiences, growth opportunities. That message, though, is actually the root reason why I landed in hot water. That message, which I broadcast louder and louder as the right never to be offended is used more and more to restrict the right to free speech, goes against the administration-backed practice of making sure the customers on the academic cruise ship always get what they want. My message is that alien viewpoints and alien styles of expression, like playing in the dirt (especially as a kid), are good for you—good for clarifying your thought, good for making you question yourself, good for checking your biases, good for spurring adventure, good for cultivating empathy and wisdom, good for nurturing depth of character and resilience—even though they can challenge the accepted narrative and thereby trigger deep discomfort! Heterodoxy is crucial for serious pursuit of knowledge. Echo-chambers are inimical to higher education. Academia should be a place for free exchange of ideas, for the collision of adversarial opinions, for open discussion even about unsettling ideas, historical events, and hypothetical situations. Encountering people who actually think differently (rather than who simply look differently) calls us to question and learn about our own perspectives, which makes us better equipped to resist letting biases cloud our vision of the truth. Diversity of thought, which allows us to remain open to the possibility that we are wrong, is a preventative against, as well as an antidote to, dogmatism (and the repression and damnation—read: cancellation—of others that has so often been sustained by it). My experiences, as disturbing as they were, have clarified my mission, which was always, somewhat ironically, to promote the idea that, for the sake of growth, we should not shut out all sources of contagion, all disruptive experiences—let alone cancel them!

Second, and for a more tangible example of how I made lemonade from the barrage of lemons, I have launched a publishing house, Safe Space Press. Safe Space Press provides home for divergent and disparaged voices (trans, addict, queer, incarcerated, black, senior, unemployable, poly, gambler, homeless, gifted, neurodivergent, disfigured, immobile, indigenous, and so on) who are critical of the excesses of cancel culture. Celebrities tend to get a career boost out of “cancelation,” which makes some people—usually the well off and insulated—doubt how real or at least how bad cancel culture really is. Truly hurt by the bitterness-driven movement to eradicate heterodoxy at any expense are the unseen and powerless, people such as myself: neurodivergent with a chronic disease, childhood spent in an illiterate poverty that continues to estrange me from, and make me seem strange to, my colleagues (most of whom are too privileged ever to get it). The guiding belief of Safe Space Press, unabashedly influenced by the humanities tradition, is that radical care and kindness—as opposed to ruining lives without due process (which effectively serves to make a prison yard out of society, polarizing people and even alienating allies)—can be an effective tactic for social change.

Silence is the goal of intimidation, and I will not go silent. Skittish and morose as I now am after my artwork has brought on so many troubles (in a land that talks a great game about free expression), melancholy and cynical as I now am after being marred on the front lines—I will not give up the fight, no matter the lust for retribution it no doubt stokes (and even at risk of succumbing myself to the same ugliness at the heart of the safe-space-cancel ethos. That said, I refuse to engage in shaming individuals who have perpetuated cancel culture—yet another reason for my reluctance to name a specific person against which I have a grievance. These individuals are to be approached with empathy. An addiction to bitterness, which has a grip on most of us but which so rages in these individuals that they form pitchfork lynch mobs, has made it—among other factors (lust for power, being the most conspicuous)—normal to (at least to pretend to) see ourselves as victims (the more victimized the better) and to set the bar on what is worthy of offense so low that we almost always have a pretense to feel that existential-angst-numbing rush of bitterness. No one said fighting the good fight would be uncomplicated.

Michael Anthony Istvan Jr., PhD

“He who will work aright must never rail, must not trouble himself at all about what is ill done, but only do well himself. For the great point is, not to pull down, but to build up, and in this humanity finds pure joy.”—Goethe (Conversations with Eckermann)

PS I will end with some important beacons of light. The first is a segment of the Harper’s open letter by Margaret Atwood (and an array of other artists and public figures standing against cancel culture).

The forces of illiberalism are gaining strength throughout the world. . . . But resistance must not be allowed to harden into its own brand of dogma or coercion. . . . The free exchange of information and ideas, the lifeblood of a liberal society, is daily becoming more constricted. . . . [C]ensoriousness is . . . spreading more widely in our culture: an intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty. We uphold the value of robust and even caustic counter-speech from all quarters. But it is now all too common to hear calls for swift and severe retribution in response to perceived transgressions of speech and thought. More troubling still, institutional leaders, in a spirit of panicked damage control, are delivering hasty and disproportionate punishments instead of considered reforms. Editors are fired for running controversial pieces; books are withdrawn for alleged inauthenticity; journalists are barred from writing on certain topics; professors are investigated for quoting works of literature in class; a researcher is fired for circulating a peer-reviewed academic study; and the heads of organizations are ousted for what are sometimes just clumsy mistakes. . . . We are already paying the price in greater risk aversion among writers, artists, and journalists who fear for their livelihoods if they depart from the consensus, or even lack sufficient zeal in agreement. . . . The restriction of debate . . . invariably hurts those who lack power and makes everyone less capable of democratic participation. . . . As writers we need a culture that leaves us room for experimentation, risk taking, and even mistakes. We need to preserve the possibility of good-faith disagreement without dire professional consequences. If we won’t defend the very thing on which our work depends, we shouldn’t expect the public or the state to defend it for us.[4]

The second beacon of light can be found in the moving words of Robert J. Zimmerman, president of the University of Chicago.

Free speech is at risk at the very institution where it should be assured: the university. Invited speakers are disinvited because a segment of a university community deems them offensive. . . . Demands are made to eliminate readings that might make some students uncomfortable. Individuals are forced to apologize for expressing views that conflict with prevailing perceptions. In many cases, these efforts have been supported by university administrators. Yet what is the value of a university education without encountering, reflecting on and debating ideas that differ from the ones that students brought with them to college? The purpose of a university education is to provide the critical pathway by which students can fulfill their potential, change the trajectory of their families, and build healthier and more inclusive societies. . . . Essential to [the process of questioning oneself and others, a critical-thinking process that the university is in place to nourish,] is an environment that promotes free expression and the open exchange of ideas, ensuring that difficult questions are asked and that diverse and challenging perspectives are considered. This underscores the importance of diversity among students, faculty and visitors—diversity of background, belief and experience. Without this, students’ experience becomes a weak imitation of a true education, and the value of that education is seriously diminished. . . . Some assert[, however,] that universities should be refuges from intellectual discomfort and that their own discomfort with conflicting and challenging views should override the value of free and open discourse. We have seen efforts to suppress discussion of Charles Darwin’s work, to insist upon particular political perspectives during the McCarthy era, to impose exclusionary acts of racial and religious discrimination, and to demand compliance with various forms of “moral” behavior. The silencing being advocated today is equally as problematic. Every attempt to legitimize silencing creates justification for others to restrain speech that they do not like in the future. . . . Universities cannot be viewed as a sanctuary for comfort but rather as a crucible for confronting ideas and thereby learning to make informed judgments in complex environments. Having one’s assumptions challenged and experiencing the discomfort that sometimes accompanies this process are intrinsic parts of an excellent education. Only then will students develop the skills necessary to build their own futures and contribute to society.[5]

Notes

[1] “Universities have an important role,” the President of the University of Chicago (Robert J. Zimmer) puts the basic point in a campus-wide letter, “as places where novel and even controversial ideas can be proposed, tested and debated” (see: president.uchicago.edu/page/statement-faculty-free-expression-and-diversity). I find absolutely toxic the growing sentiment that “universities should be refuges from intellectual discomfort” and that protection from discomfort “ should override the value of free and open discourse.” Zimmer lays out the point well (see: wsj.com/articles/free-speech-is-the-basis-of-a-true-education-1472164801)

Universities cannot be viewed as a sanctuary for comfort but rather as a crucible for confronting ideas and thereby learning to make informed judgments in complex environments. Having one’s assumptions challenged and experiencing the discomfort that sometimes accompanies this process are intrinsic parts of an excellent education. Only then will students develop the skills necessary to build their own futures and contribute to society.

[2] When I waked up just at daybreak [Jim] was sitting there with his head down betwixt his knees, moaning and mourning to himself. . . . He was thinking about his wife and his children . . . and he was low and homesick . . . and I do believe he cared just as much for his people as white folks does for their’n. It don’t seem natural, but I reckon it’s so. . . . He was a mighty good nigger, Jim was.

[3] Jim said it made him all over trembly and feverish to be so close to freedom. Well, I can tell you it made me all over trembly and feverish, too, to hear him, because I begun to get it through my head that he was most free—and who was to blame for it? Why, me. I couldn’t get that out of my conscience, no how nor no way. . . . It hadn’t ever come home to me before, what this thing was that I was doing. But now it did; and it stayed with me, and scorched me more and more. I tried to make out to myself that I warn’t to blame, because I didn’t run Jim off from his rightful owner; but it warn’t no use, conscience up and says, every time, “But you knowed he was running for his freedom, and you could a paddled ashore and told somebody.” That was so—I couldn’t get around that noway. . . . I got to feeling so mean and so miserable I most wished I was dead.

[4] https://harpers.org/a-letter-on-justice-and-open-debate/

[5] https://www.wsj.com/articles/free-speech-is-the-basis-of-a-true-education-1472164801