Istvan Bio 15

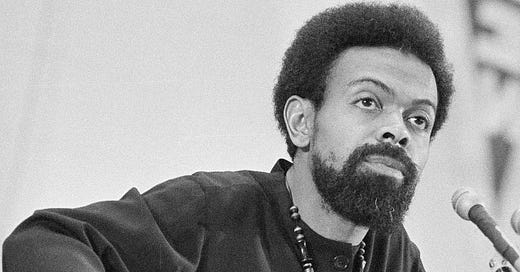

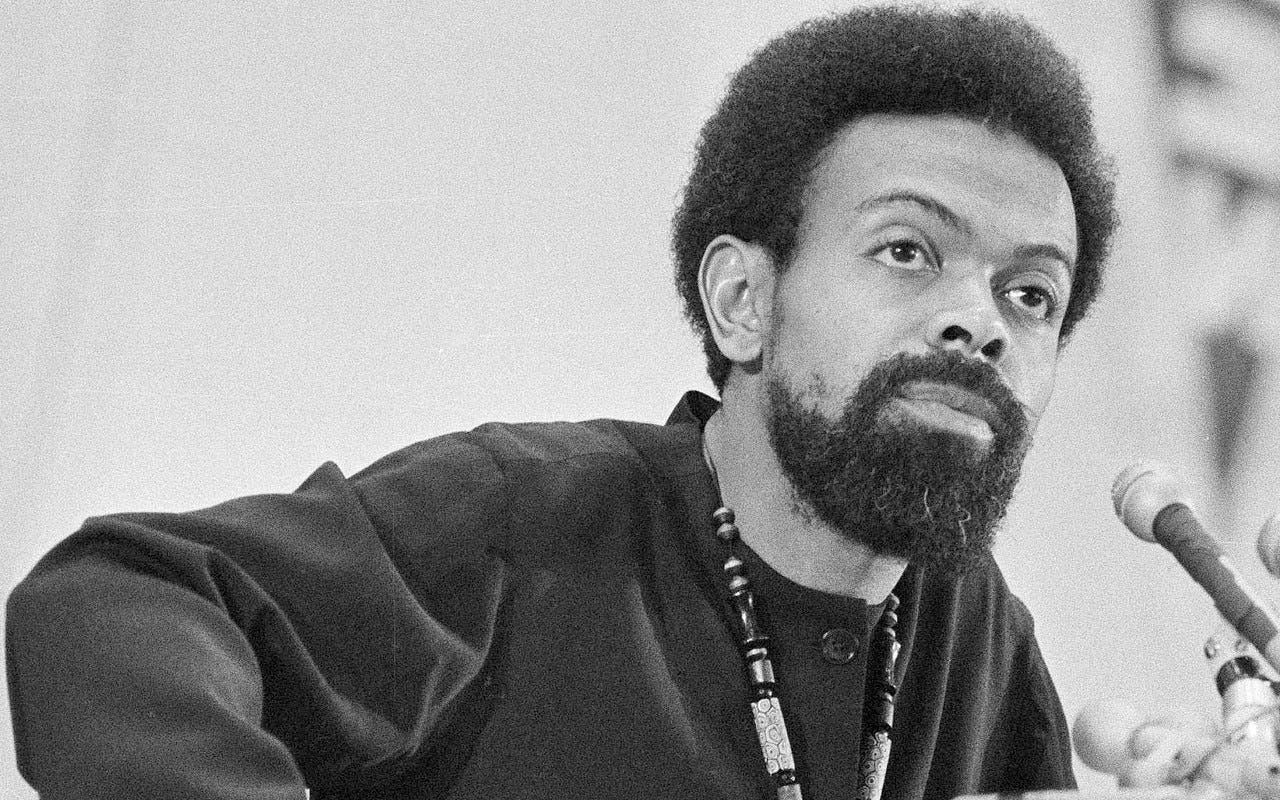

Let's workshop this author bio about a poet who embodies the audacious spirit of Amiri Baraka, striving to illuminate the brutal realities of the world with an empathy that teeters of monstrosity

M. A. Istvan Jr.'s poetry erupts as a molten flow of excremental energy, a fierce furnace incinerating—even when flameless—the curtains of safe-space modesty. He does not cower from cobwebbed corners, even his own. He is not afraid to provide a soapbox for disturbing voices so many prefer to muzzle—if not also deadbolt behind boarded-up doors—like some da-da-da down-syndrome daughter ever drooling in the 1950s. Thumbing at random through his works, it is hard not to see in such audacious inclusivism Amiri Baraka as a poetical father.

Rape the white girls. Rape their fathers. Cut the mothers’ throats. Black dada nihilismus, choke my friends . . . . (may a lost god damballah, rest or save us against the murders we intend against his lost white children).

But one gets the sense that, beneath even his most militant and searing verses, Istvan ultimately just wants to put what he sees in paint. His core audience, if this is right, is not those he hopes to persuade and rally or offend and terrify, but rather those Nietzschean life-affirmers he hopes will stand in appreciative attendance to what he says, perhaps here and there highlighting the key points and dramatic shifts in song cast into the tempest like some Attic chorus of ancient Greece. Since his brushstrokes, even when of bleeding wounds, seem born of celebration for the full spectrum of reality, attentive readers cannot help but feel a sense of metaphysical solace in the heart of the most unnerving content—as one seems to, for example, beholding Felix Nussbaum’s concentration-camp self-portrait with a man in the background shitting in a barrel.

What strikes deepest is Istvan’s ability to step into the shoes of those supposed to be his enemies. Without tipping into someone too cowardly to tell others what he really thinks, he is not naïve enough to overlook the goodness in anyone with whom he disagrees or to fail to see himself in them even at their Nazi worst. Those few willing to read him with the care he deserves understand that even the darkest and most aggressive content is tempered by heartfelt sincerity verging when appropriate on sentimentality.

Socio-political agendas do ring through Istvan’s work, yes—especially after having been disrupted in his Hogwarts tower from his metaphysical musings by the anti-art anti-diversity flood of cancelation spewing even from his own colleagues: fake progressives who, in droves around 2016, revealed their true identities as, if not followers of Voldemort all along, too afraid not to bow at his feet. These agendas, however, never turn so ruthless as to have him lie about what he hates or to have him lie about what he loves. They never have him deny his ultimate love for what he hates—what he hates being, in his mind, just another flower of a Spinozian-Leibnizian reality than which there can be, all things considered, no better: whether cancer and nuclear bombs, or “finned sharks tossed / overboard” and “toddler bukkake by bandanaed Bloods.”

Take that last terrible image, for instance. The whole stanza from which it is plucked summarizes the penetrative potency of this watchman’s lantern.

toddler bukkake by bandanaed Bloods only ever dipping into her suckling mouth out of an undeclared decency irreducible to the base fear of not wanting to get caught

Repulsion fails to blind Istvan to the spirit of care operative in the misguided hearts of these twofold gangbangers. His poetry, as much as it has its golden dawns of serenity, is not the place to go for easy answers and comforting lies. In stark contrast to all the social-media memes reinforcing the notion that what is true is whatever one feels is true, that concept “my truth”—the most sinister of all the sinister watchwords of the Gen-Zodiacs of Carl Sagan’s demon-haunted visions—finds no safe harbor in his soul.

This piece is unpublished