In Case You Are Mad at Me

Let's workshop this post that provides some context for my stance on the obscene--particularly, hypersexual--lyrics dominating mainstream rap music

In Case You Are Mad at Me

A few things should be clarified right away, although I will go into the nuances later. And please note that this post is written in great haste.

(1) I do not hate anyone at all, and this includes the people who make obscene art.

(2) I am not against “obscene” art in itself. I am not against music lyrics that are hypersexual and hyperviolent. In fact, my essay “An Apologia for Biggie’s Child-Rape Lyrics” defends vile rap lyrics from calls of censorship, showing that even in the worst cases there are redeemable qualities.

(3) In my Sukihana piece, which you must understand is just a sliver of a document that sits currently at almost fifty thousand words, I do cite the important voice of C. Delores Tucker, a civil-rights activist known for marching with Dr. King early in her career and crusading against the hyperviolence and hypersexuality of mainstream. However, I do not agree with her on everything—particularly, not on her would-be call to have Sukihana’s music banned as a matter of public safety and the preservation of black dignity.

You must be careful in thinking you know where I stand merely based on the scenes depicted in my snapshots of the world. You must be especially careful when you already know I myself often depict unsavory facts about reality in my art (murder, rape, and so on). Are you not going to give me the benefit of the doubt? I am not so audacious as to stoop to obvious hypocrisy. Come on now!

I will admit that I am sickened by mainstream rap music today. Although there are some underground exceptions (Myka 9, Abstract Rude, Eligh, and so forth), when I look back at the rap music from the past that I loved, I am largely sickened there as well—although not to the degree I am today. Being around so many younger people I have had to try to reconcile my anti-censorship orientation, my pro-artistic-expression stance, with the reality of my distaste and my awareness, especially as a father of a young boy, as to how toxic some of this music can be. I have a real problem—Aspergers style perhaps—with hypocrisy. And I especially hate how a lot of this “ratchet” music dominating the airwaves is glorified in black communities when it is obviously a blight—managing to perpetuate so many vile stereotypes of white supremacy because it is so mainstream, its content in more and more cases ghoulishly aspirational for young people.

How have I handled the conflict? Well, the slogan I say around the house is that “it is not so much what they are saying, or that they are able to say it, as that it seems to outshine all the other sorts of content reflective of other ways of being black.” I put it this way in my “Letter of Grievance”, which is an open letter to my university for terminating me abruptly for my own “obscene” artwork (again, another reason why it goes against my nature to try to cancel Sukihana). In this excerpt, I explain a piece of performative art I made, a video in the voice of one of my characters (Mrs. Tong), responding to the song WAP.

The point of the Tong video is to dismantle the monolith of black hypersexuality (through the backdoor-guerrilla means of satire). The main role of black women, so at least goes the entrenched and reinforced caricature, is to serve as primal sex object. No wonder, then, that one of the main ways for black female musicians to inveigle themselves into the good graces of our society (so that they can sell sell sell) is to act out this cultural fantasy. My Tong video was a response to the song “WAP,” where Cardi B and Meagan the Stallion—or, perhaps more accurately (and to extend to these artists the fairness that should have been extended to me), the whore characters they are playing—celebrate having their various canals “beaten up” so roughly that the men doing the beating are urged (yes, by the beaten themselves) to risk catching assault charges. Seeing so many young people so uncritically celebrate this song, my goal was to shine a light on how it perpetuates an unfortunate stereotype. More specifically, my goal was to provoke self-reflection, particularly the self-reflection of those who just eat this song up and yet who claim, at the very same time, to stand firm against the hypersexualization of black bodies. (Insert “hmm” emoji.) Those from the population in question I knew would be jarred to see Chinese women, themselves targets historically of the hypersexuality stereotype, trying to compete with black women as to who is, in effect, the bigger—more lubed and ready—tool for sexual pleasure. In having Tong say—and here we have again another instantiation of the naïve-narrator literary device—“Chinese women have most wet ass pussy (even more than Stallion B),” the hope was to make my target audience see their potential cognitive dissonance on this matter.

Do not get me wrong. First, I am a sex-positive feminist who supports liberated female sexuality and sex work as real work. Second, and as a shocking artist myself, I will never interfere in the free expression of shocking artists—yes, even if their lyrics glorify being a whore and welcoming bedroom treatment so rough that the men “catch a charge.” However, it is crucial that diversity be depicted. It is crucial that young people of all stripes do not grow up thinking what for so long our national culture—through much more than just the spread-eagle Lil’ Kim posters (in my own teen room)—has hypnotized them into thinking: that the main role of black women is to function as twerkbots of gratification, not as feeling and thinking citizens with assets beyond ass. I want to see more variety with women in hip hop. Standing up for true diversity, which is more and more a main mission in my life (and factors largely into the issue of my termination), is the purpose behind the Tong video. (Defending diversity is so important to me, in fact, that were we in a society where the stereotype was completely flipped—a society, in effect, that regarded black women as asexual creatures who loathe anything having to do with sex—you better believe that my artistic efforts would be devoted to exposing the ridiculousness of that as well, shattering the monolith!)

So I reconcile my unease at the stereotype-perpetuating (and antisocial and nihilistic) lyrics, on the one hand, with my own “obscene” art and my endorsement of artistic freedom, on the other hand, by saying that my gripe is mainly with the lack of diversity in mainstream music. It is the monolithic representation of blacks in mainstream music that presses my buttons. I yearn for a richer tapestry of voices that challenge and redefine prevailing stereotypes. The end of the excerpt suggests, in fact, that I would welcome a Sukihana voice in different times.

I might be understating my case a bit, however. There seems to be a difference between my own obscene art and the obscene music in question. With rare exception, there is an obvious distinction between my own person as the artist and the characters in my art that sometimes do vile things. Even when I use the first-person point of view, there is an understanding that it is the narrator not me (the author) speaking. Of course, the same charity should be extended to rappers too. And I do grant that, by default (unless, I guess, told otherwise), rappers are not speaking in their proper voices even when they talk about killing and raping. That is why I oppose using rap lyrics in court against artists.

Artists have always brought dark themes into the limelight. I am no exception. I delve into issues of murder, betrayal, and insanity. But one difference does stand out, which might be relevant especially when we consider the young audiences of this music. Unlike in my work, where the narrator does not glorify vileness (unless the narrator is a character in a larger story), there is a persistent essence of glorification of vileness, of bragging about it, running through these rap lyrics. Especially when we see the actual artists coming out in the public with the breast augmentations and Brazilian butt lifts that they bragged about in their songs, it is hard not to see them as speaking in their own proper voice.

What matter is it if they are speaking in their own proper voice? What difference does it make if they really are the unquenchable beasts they play on TV, ready to reduce everyone they encounter to carnal objects (which more of them are now, given the collective grooming)? Perhaps nothing in itself. It would be idiotic of me to say you cannot do vile art if it is in your own proper voice. Although I do worry about the kids. The kids look up to these stars. As if the content itself were not bad enough given that swamps the airwaves (drowning out the alternative black voices), the influence power increases when the actual silicone-and-blood people they look up to are saying “Yep this is me: I’m proud of it and I’m cool as shit because of it.”

Twenty years ago it was a shame to see black people represented so horribly on daytime talk shows: ripping off each other’s hair hats as they fight about who is the real “baby daddy.” But now it is on every song that I hear around me. More dripping pussies needing to get pounded by married me so the owner can pay their rent and have some extra money for Percocet. Perhaps I need a new environment, new people around me. But it just seems that it is everywhere I turn. I hate to see black people done dirty at every turn. I hate to think what influence this is having.

Think about it. The prime targets of these popular depictions are the youth: malleable money-spenders whose lifelong thought-and-behavior patterns and understanding of social norms are still baking in the oven. It is hard to imagine that these hypersexual songs would not promote casual sexual activity (perfect for more underage black mothers of poverty). I hate the idea of yet another generation of blacks groomed to feel and think and act in the stereotypical ways. I hate the idea of yet another generation of people, black and white, will find it difficult to picture black bodies without also picturing extreme sexual organs in extreme sexual situations of dehumanization. I hate the idea of yet another generation of people, as if we were back in antebellum days where sexual allure and guesses at potential fertility factored into auction-block sales, will deny sexual innocence to black girls, continuing to link their bodies to lust (such that, to give the clearest proof of the point, a depiction of the Virgin Mary as black would read at least subconsciously to blacks and whites alike as blasphemous, the mere darkening rendering the purest woman a freak-a-leek jezebel). I hate the idea of yet another generation of black boys and black girls believing that their primary value resides in their sexual organs and that their desirability lies foremost in being voracious in bed. I hate the idea of yet another generation of white people feeling—and with increasing odds of being proven right!—that dating a black person will be like an exotic escapade “in the wild” (potentially a Percocet-filled ghetto-gagging anal-gapping adventure) with someone who must have a lot of experience (especially if they are really dark and have a lot of curves). I hate the idea of a new generation of everyday black people, when they fail to live up to the suffocating ideals of being magically irresistible or being big-dicked dominators or being ever-dripping and so every-ready to pole ride or so on, finding themselves mentally terrorized into confusion and into self-loathing feelings of inauthenticity and excommunication.

These anecdotes aside, I did say that even the most gruesome lyrics have redeemable qualities. I am trying to play fair while also respecting my unease and what I know to be true: that these lyrics are harmful, especially when they are constantly driven down the throats of youth who see no alternative representation of how black people can be (aside from insatiable fiend for sex and drugs and violence). Consider, then, the following except from “An Apologia for Biggie’s Child-Rape Lyrics”, which talks about the redeeming qualities and sheds a good deal of light on why it would be a mistake to lump me in with some bigot who wants to ban rap music.

One thing needs to be said right from the jump. On top being incentivized by an industry that sees big-money value in sexual shock (especially from black mouths), rappers with sex-heinous lyrics are most often young and thereby not only more sexual but also more prone to engage in boundary pushing. Boundary pushing, characteristic of hormonal youth, is essential for keeping that precarious social balance crucial to our thriving, the balance between adventuring-progressive energy and cautious-conservative energy. For finding new meaning and restoring renewed appreciation for old meanings, it is important to explore beyond the walls given to us at birth from the explorations and upkeep efforts of past generations. The youth dare to plunge into chaos. They are open to the contagion of diversity. They are the creative-visionary side of humanity: a side necessary—although not sufficient—to being the adaptable creatures we are; a side necessary—although not sufficient—to our flourishing (if not to our very survival). To be sure, we need the conservative side too. Without order, without a border-walled homebase of custom and security, there can be no adventure in the first place. A bird first has to be cared for with regularity before it can leave the nest. And it needs a nest of regularity to come back to. Once a new territory is opened by the visionary youth, the conservative spirit is crucial to making that new territory a stable home, to nesting it, to managing it. Balance is crucial, though. Too much traditionalism, too much sticking with old ways, too much safety in some incubator bubble, and we become rigid and inbred and unable to handle the anomalous. These young rappers, in exploring beyond the walls of taboo, in the very least exercise a muscle important for a healthy society.

It would not be unreasonable, however, for someone to say that—true as it might be, in effect, that these rappers are fulfilling the adventure-seeking part of the balance between chaos and order—some boundaries, for the sake of the stability of our families and communities and country, should not be pushed. . . . [But l]ook into your heart. Be empathetic, especially to the young person you once were. If you do, I think you will see that these rappers are largely just messing around. They are playing with shock, yes, to draw attention and to stand out (and thereby to make money). But they are playing with shock also for a more fundamentally human reason: to explore for themselves—in the safety of a mere simulated reality—what it is like to cross the limits. Being allowed to play with all sorts of fantasies, dark as they sometimes can be, seems crucial to our very humanity. It seems crucial, that is, to our being those beasts with the freedom to envision the wildest scenarios—the freedom that allows us to foresee and adapt and innovate, that allows us to question our norms and resist stifling status quos, that allows us to foresee the dangerous possibilities of going down certain paths, that allows us to understand who we are, that allows us to experience and learn the lessons of diversity with less risk, that allows us to feel renewed hope, that allows us to discharge our bestial forces in healthier ways. . . .

We are strangers to ourselves. The fact that Nazism spread through so many regulars testifies to the envy-driven bit of Hitler we all have in us—the cruel bit we deny and suppress, the amazingly-ancient vicious bit we project onto others, to our own detriment (to our own detriment at least in the sense, to speak by analogy, that it would be a detriment for elementary schools never to practice fire drills on the assumption that “fires do not happen here”). Biggie and so many other rappers, in reminding us of our ruthless and toxic parts, serve to keep us honest with ourselves—honest about how we are not as saintly as we present ourselves or as virtuous as we assume we are. This way we have a chance of being less fragmented as individuals. This way we are better prepared to handle rocky times. Biggie and so many other rappers, in reminding us of the shadow elements we are ever tempted to say belong to others, serve to keep us on guard from becoming their slaves. This way we can make more informed decisions about how best to engage in the world. This way we can even draw upon our dark sides for positive ends (as does a person who, to give an extreme example, uses his firsthand knowledge of serial killing to help police capture serial killers). Awareness of our dark parts in most cases increases the chance of finding nondestructive (if not healthy) outlets for them—outlets such as creating fantasy rap lyrics instead of actually hunting down [an eight-year-old girl like Biggie mentions in his song]!

As a kid I always wrote C. Delores Tucker off, following Tupac and other rappers, as an “uppity cunt.” She was the archenemy of hip hop, my culture. I have come a long way since then. I share a lot of her worries. She is right to see mainstream rap—and if only she could see it now!—as antisocial and nihilistic and consumerist music that, being delivered especially in a glorified-aspirational way and dominating all other forms of rap, successfully perpetuates animalistic stereotypes of blacks and inspires the emulation of children who want to be as cool—at least half as cool (which is bad enough)—as their musical role models.

I do not go as far as Tucker, however. Her core solution seems to be to ban obscene rap. She has protested its sale with as much urgency and dedication as she opposed segregation, worried of the dangers of children (especially black children) hear Snoop calling women “hoes”—perhaps never imagining that the woman themselves would a few decades later call themselves hoes with pride and revel in their homewrecking drug-use and their sleeping around, constant pregnancies no biggie when there is always plan b. Aside from the personal reason that I am an artist first (and get sick to my stomach by the idea, at least the abstract idea, of any art being banned), there are two more sober reasons why I do not go as far as Tucker.

(1) I would be a hypocrite if I said we should ban artists for being obscene. My own material, after all, veers often into the obscene. No, I do not glorify the dark corners where my light shines (which is unlike what seems to be happening with a lot of mainstream rap). But still, like a journalist or a photographer or even a true-crime podcaster, I hold up a mirror to all of us (including myself)—our actions and desires and beliefs. What reflects back, of course, is not always beautiful and inspiring. Sometimes it is downright awful: homewrecking awful (“I’ll steal your man though and fucking beat your ass in front of your kids hoe”), humans-reduced-to-sex-crazed-gremlins awful (“Ain't gon' let me fuck, and I feel you / But you gon' suck my dick 'fore I kill you”), humans-drugging-and-plastic-surgerying-themselves-to-look-and-think-like-orcs awful (“You can block my number, but he still gon' eat my ass / He just paid for my titties, that's why you bitches mad / I suck dick like a champion when he put the Perc' in my ass”).

(2) As that last point might indicate to several readers (perhaps readers who do not find obscene the botoxed face and the drug-riddled minds that more and more people are starting to wear as a point of pride), what counts as obscene is going to change according to who is doing the judging. The danger, then, of banning the obscene is that whatever the powers that be regard as obscene could be banned. That should seem scarier than not banning obscene speech. To put it in perspective: surely many people at the height of segregation thought it obscene for a black boy to be swimming in the same pool with little white girls.

Where I do agree with Tucker is that the antisocial and hypersexual and nihilistic music, the mainstream rap that is all the rage today, is harmful for the world at large (and black Americans, in particular). As she puts it: “What do you think Dr. King would have to say about rappers calling black women bitches and whores? About rappers glorifying thugs and drug dealers and rapists? What kind of role models are those for young children living in the ghetto?” Although I am not convinced that mainstream rap music plays as intense of a role in harming the black community as Tucker thinks it does, I do agree that the antisocial message being so dominant and the music being so hypnotically manipulative (as people as wildly different as Plato and Kanye West would say) plays a big role. She puts it as follows.

[T]hrough the lyrics of rappers who display no respect for women, no respect for families, and little respect for themselves, the souls of our sisters are being destroyed and so too their progeny. All of us have watched as the industry has grown. We have watched not really knowing, not really understanding, not first realizing the damage that is inherent in what some thought were merely words. Now we see the direct and indirect effects. We see the rise in murders, in abuse, in batteries—teen prostitution and teen suicide. We hear the wailing mothers, the grieving sisters, the tormented brothers and fathers and children planning their own funerals.

I also agree with Tucker that, although the youth are the major purveyors of this antisocial music (and as such are to be resisted), they are to be resisted with compassion whenever possible since they are reflecting largely what was taught to them by the previous generation. Tucker puts it as follows.

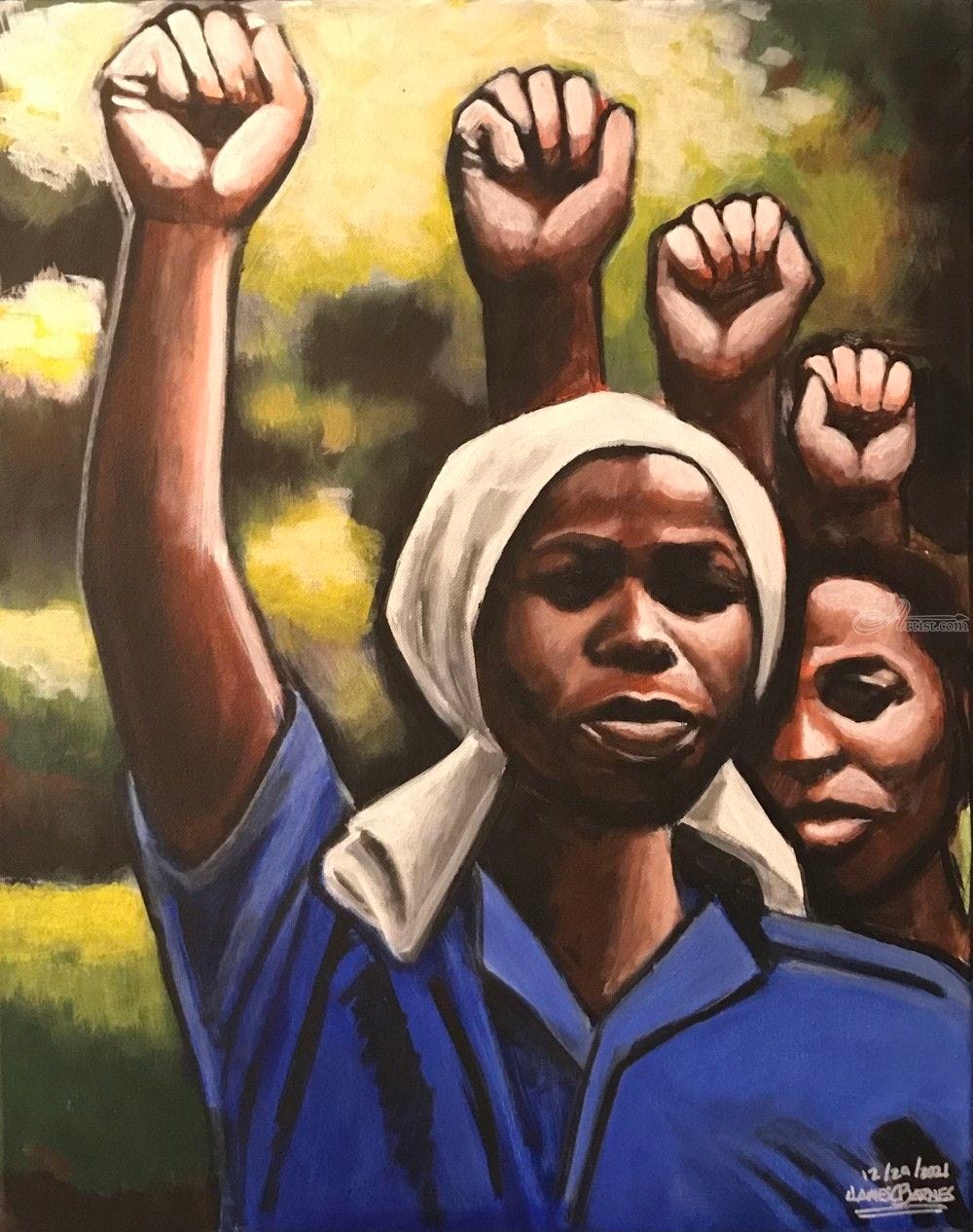

We marched for our rights to Selma (I was there with Dr. King), were beaten with Billy clubs, and were bitten with dogs unleashed by bull collars. We did not tolerate injustice and insults from our worst enemies then, and we sure ain't gonna accept insults from our youth now! Although [my organization] condemns the actions of those young people who produce such music, we also realize that . . . they are not the root causes of the complex socio-economic forces that are manifested in such vile entertainment. Those problems were there long before many of them were born.

The youth, even the ones at the forefront of spreading this antisocial music, are to be approached with empathy since they are largely acting out—tantruming, in some senses—against the situation they have inherited and the downward trajectory that the US is in. At least that is something one could say. Yes, that would not explain it all. There are many people worse off in the world than kids in the US, after all. A big factor, of course, is that the world incentivizes it. Just as bodybuilders must use steroids to be competitive at the top levels, to sell rap music in this environment it is hard to resist going down the path of “selling your soul to the devil,” as Sukihana put it a few years ago.

There is a greater horror, however. It is not like all these kids are saying to themselves “Damn, its unfortunate I have to represent myself as a sex-crazed gremlin to have a chance in this industry.” More and more have largely internalized the gremlin approach. They have been groomed from the womb basically, at least in so many cases, to value it. It increasingly has become normalized. Just as much as Cardi B’s or Sukihana’s children are going to grow up thinking it is normal—and even enjoying—that woman look all puffy in the face and have huge lips and butt implants like they are walking around with Instagram filters, the youth learn from the messaging in the music what black people value (sex and drugs and violence) and what black people fundamentally are (jungle animals, sex objects, infinite fuck spaces). Indeed, if we magically took away all the incentives for this gremlin music, it would continue on due it its own momentum for awhile at least. It is internalized.

Since I do not agree with Tucker’s core solution, which is to ban the black-hobbling music from the airwaves, what other solutions are there? Well, Tucker herself has supplemental solutions. In general, she thinks that we must provide other channels for rap artists to use their musical and linguistic talents in a more “positive and wholesome way.” Tucker has more specific solutions as well.

First of all we must use all means possible to eradicate and ban the sale of illegal guns. We must remove guns from the hands of our children and our “gangsters” who are so proud of the power of the gun. That's number one. Number two: we must reinvent our educational system to include more vocational training to provide a successful transition between school and work for those who will not continue to go on to college. We must extend the school hours in the school year so that latchkey-children teachers will be from their schools instead of from the street. We must provide educational opportunities for our prisoners so that they will be productive citizens when their tour of prison is over. . . . We must provide community outreach so that our youth who have embraced the gangs as their only family will find refuge in community institutions neighborhood academies and educational programs. Convert our unused military bases into institutions of peace where men and women can be trained to become productive citizens who will contribute to the well-being of this nation, expand our nation's infrastructure where needed, and make this nation of powerful global force.

Are there any other solutions? Here are a few, still in brainstorming phase (like this whole post, really). Many of these overlap in my haste. We do need a multifaceted approach that combines both systemic changes (like improved education) and cultural shifts (promoting critical thinking and alternative art forms).

Restricted access.—I am much more open to restricting access to art than I am to banning art. It might be hard to carry this out, technically. And it might involve government interventions that makes many people, including myself, feel uneasy. It is an age-old problem. Ideally, we want people to stop buying all this soda on their own since it is burdening society with all the medical problems that result. But when they will not stop on their own, it does seem wise (considering the whole body politic, if that is something we care about) to restrict their ability to buy a fountain soda over a certain size, say—however much, again, that rubs the rebellious child in me the wrong way.

Counterincentives.—I am open to incentives to limit some of the negative impacts of the music. We could incentivize, in general, not being so sheepish. Everyone wants to be like everyone else. That is a high value in our culture, even when we deny it and even when we think we are being unique by going to Burger King instead of McDonald’s like the people in our friend groups. If we incentivized deeper nonconformity, perhaps that would lessen the amount of youth aspiring to be the same hypersexual and Percocet-popping way as everyone else. When I speak about counterincentives, though, I especially have in mind incentivizing rappers to focus on other things aside from sex and drugs and violence. No Name once said (although I am paraphrasing) that people, especially white people, love to go to festivals and dance to the music of black depravity, the music that makes black people look ridiculous and immoral and superficial and consumerist and superstitious and violent and all botoxed-out to the Jacko-Sukihana point of being constantly puffed and so on. But if we can incentivize other voices, just as we incentivize clean-energy technology to try to resist the worst of climate change, perhaps over time we could all be swaying at festivals to more prosocial content—like the following song from Abstract Rude.

Education.—Vile lyrics in rap do play a well-evidenced role in encouraging vile behavior among impressionable youth. But the issue, as I suggested above, might be less about the lyrics themselves, or even about their troubling monopoly over the billboards. Somewhat analogous to the pitiful sex-education in certain abstinence-only communities in the southern US, the issue might be more about our culture’s pitiful efforts to prepare people (especially kids) for handling these lyrics—efforts whose pitifulness is sustained, heartened, by the notion that censoring and silencing artists are the only ways to go. We should perhaps teach the youth that the antisocial music is not really representative of the artists themselves (although, as I suggested, this is starting to change with more and more artists buying into their own act, like Tupac bought into Bishop, and actually doing the drugs and actually doing the violence). The education might involve reinforcing the difference between painting a picture and endorsing that picture, the difference between shining light on horror and advocating for that horror. That is needed in our world. So many young people, and I have encountered many as a professor of philosophy for over a decade, are unable to separate the art from the artist. On the one hand, many would actually think—as bogus as this is, and as sad as this makes me for humanity to say it—that Bach is no longer a genius musician if we found out he raped puppies. We are a world where people actually hate the actor because of the role he played. Critical thinking, in general, needs to be emphasized so that we can restrain our monkey impulses from making such leaps. So many regular people in the West fail at even the most rudimentary reasoning.[1] How, then, can we expect them to digest these lyrics or understand them as something not to aspire to? Of course, much of this education needs to come from the family. The problem is that, and Tucker really likes to hammer on this point, the very music itself is harming families, breaking them apart with violence and adultery and lying and substance abuse and superficial connections all glorified.

Critique and counterart.—In my own academic and creative writing I expose the dangers of mainstream rap music, how it contributes to black debasement for example. Satire as well as critical essays, which touch upon the root influences of such art, are another solution to the dangers of this music, then. Helping to wake people up—that is my intent at least. Instead of insisting (despite all the cancel-culture rage of today) that this music be banned, I expose the issues with it. I try to make people reflect on what they are listening to around their children. It is hard to get people to do that, of course. Who wants to learn that something they like is so harmful? I myself hate to learn of the factory-farm torture behind all the meat I eat. Who wants to lose their connection to a community? A connection in depravity—"yeah nigga suck this cunt, Imma fuck your son too when I’m done / rob the whole house cause a hoe need some drugs”—is a connection nevertheless. But this is exactly why the outsider, why diversity (real diversity, not the DEI sense of bogus diversity), is so important: it makes us reflect on what the hell we are doing. It makes us question ourselves and our ways. It prevents us from going the way of the British bulldog: stale and inbreed and dumb. We might learn that we are not parenting the best. We might learn that we have no basis for believing in the healing power of crystals. We might learn that other people in the world, although equally religious, do not accept Christ as God. Painful as it all can be, it is often good for us. And it is very much needed in our time of intense conformity—a time so resistant to the outsider and to diversity that we think it a matter of mental health, as we see from social-media memes, to ban anyone from our lives as “toxic” who does not agree with everything we do, who fails to affirm “our truth” that we are a furry or a mermaid or woman or whatever, who prods us to be better, and so on.

Awareness.—Engaging artists and industry stakeholders in the conversation is vital. Encouraging self-regulation and raising awareness among artists about the potential societal impact of their work could be another path towards mitigating some of the negative effects without infringing on artistic freedom. While artists should have the liberty to express themselves freely, there is also a need for broader cultural introspection about the messages being proliferated and their real-world consequences.

I wrote this list—indeed, the entire “essay”—in haste. But I will think about more solutions.

One might wonder, though, if I would ever be open to banning an artwork itself—say, in dire situations (like, for example, a piece of music that drives many people insane). The artist in me says live by the art and die by the art: if art kills us, so be it.[2] But on sober reflection, the Nietzsche on my shoulder—who likewise warns against scientific and philosophical findings being broadcast widely even to people who cannot handle such findings—says “That is not too hygienic of you, Michael.” Yes, there is a noocratic or epistocratic side of me that says that for the good of the bodily politic it might be best to ban some expressions. If all the wisest (the philosopher kings) agree that a certain artistic expression would be deleterious to the body politic, it would seem stupid to still let it run free.

But maybe I can satisfy my artist-expression absolutism side, without sacrificing my respect for doing what is wisest and most hygienic for society at large, by saying that the creation of the piece of art in question (say, that insanity-making piece of music) is not to be banned but the distribution of it is to be limited to only those who have the stomach for it. Such musings are largely academic, though. I do not foresee many rap lyrics having such a directly harmful effect. I imagine the other solutions can be used to limit the harm without banning the art itself.

Notes

[1] There are 10 cases below. The numbered statements are called “premises.” The unnumbered statements, preceded by the word “therefore,” are called “conclusions.” For each case, answer the following question: is the conclusion true if—that is, assuming that—the premises above it are true? (So, for example, you would write “Yes” next to the following case: “1. p. Therefore, p.” You would write “Yes,” of course, because the conclusion must be true if the premise is true.)

1. John is a donkey only if Sam is a whoremaster

2. John is a donkey

Therefore, Sam is a whoremaster

1. Either A or Q

2. If A, then Z

3. If Q, then X

Therefore, either Z or X

1. If A, then Sam is a hellhound

2. A

Therefore, Sam is a hellhound

1. If Napoleon was a general, then Napoleon led men into battle

2. Napoleon led men into battle

Therefore, Napoleon was a general

1. All dogs are ants.

2. All ants are mammals.

Therefore, all dogs are mammals.

1. John is a whoremaster

Therefore, John is a whoremaster.

1. If p, then q

Therefore, if not q, then not p.

1. Either A or B

2. It is not the case that A is true

Therefore, B is true

1. Not p and not q

2. If x, then p

3. If o, then q

Therefore, not x and not o.

1. If Hitler is a selfless philanthropist, then Hitler is a good person

2. Hitler is not a selfless philanthropist

Therefore, Hitler is not a good person.

1. Not x and not o

2. If x, then p

3. If o, then q

Therefore, not p and not q.

[2] This especially brings up the issue of what art even is. On a wide conception even banning artists is a form of art