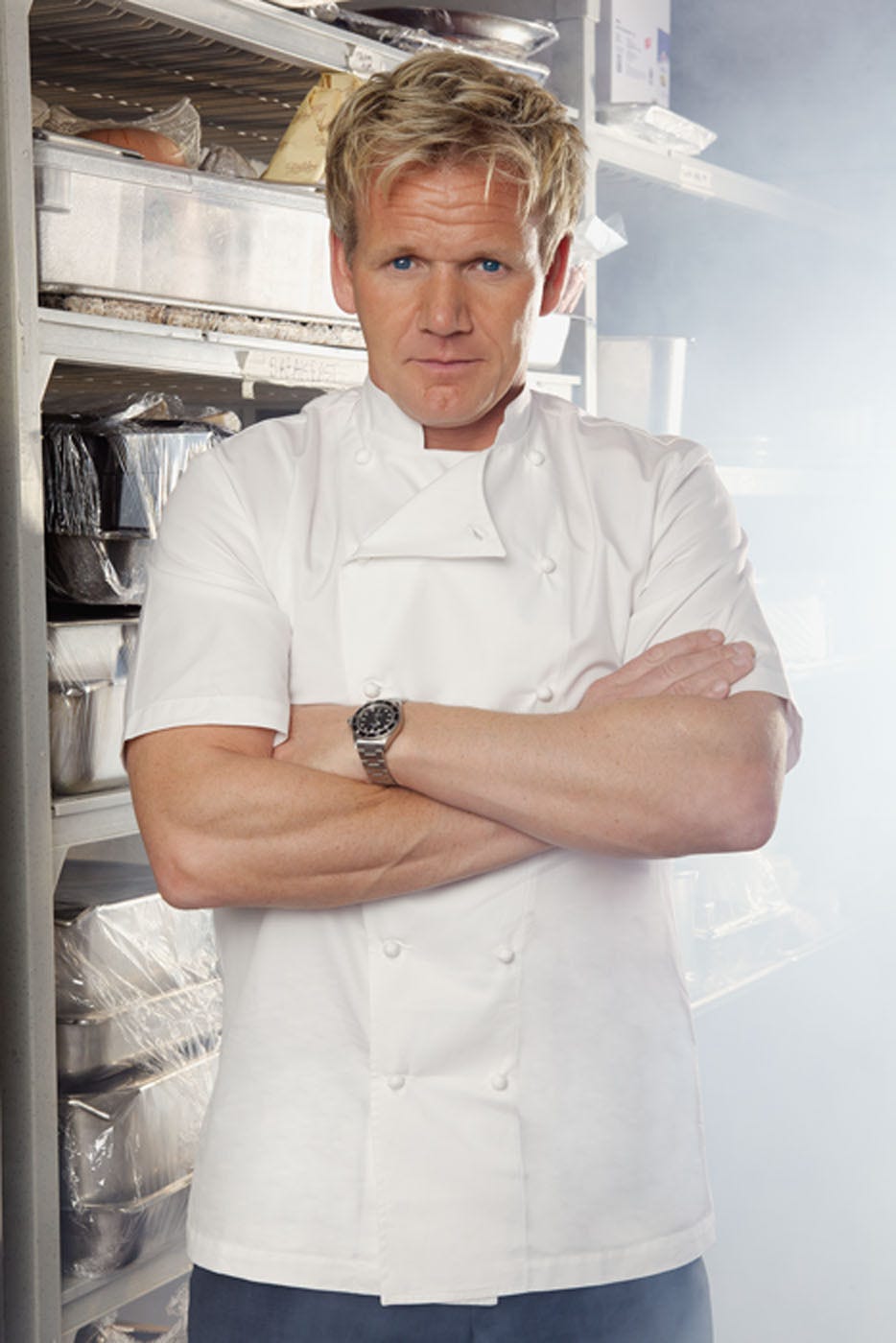

Gordon Ramsay (ROUND 4)

Let’s workshop this poem that imagines Gordon Ramsay as a groomsman who struggles to keep still.

scent of the day: Ambre de Coco, by Areej

Still only have scattered notes on this one.

This gives me the musty antique wood feel that I crave, bent in the chocolate direction I feel at the base of the Cambodian oud in several Ormande Elixirs like Ta’if Elixir, which should answer doubts about the reality and the quality of the oud used there. / musty spices very antique feel cacao powdered ancient wood. / The spices are not boisterous in the way that I hoped, but that is okay—I am pleasantly surprised any way and I have the remarkable Gujarat to get my boisterous Shamama-like insanity / I am surprised also because one of the worries, a small one (because I was prepared to smell like high quality Areej chocolate), was that this would be too gourmand, but it is not—the cocao, like the spices, are too musty-woody for that (if anything it is like uncovering an old tin of baked chocolate from the 1800s, usually there your first instinct I would gather is not yum) /

the peach is subtle and much less orchard picked than a skin fuzzy not only with the hairs of its own intrinsic nature but with the dust of an attic—and yet the skin still feels by some magic pliant, which is why I feel a more accurate way to describe this as some tree of reruit of a tree in some Vega-orbiting fantasy world straight out of the imagination of Carl Sagan/ the cocoa absolute is dry, powdery, faintly bitter, much more raw cacao husk than sweet chocolate—emphasis on the husk, antique husk (sort of like the difference between sweet vanilla and woody vanilla) / the peach and the cocao together is by no means a crowd-pleasing fruit-gourmand flourish but rather a signal of dusty antiques and a bitter-fruited whisper that functions like a faint glow at the top of a labyrinth /

the centerpiece of the fragrance is the moderate splash of shammama attar, an attar where dozens upon dozens of herbs and spices are steeped in sandawood oil to make for an oily brown-spiced medicinal treat / the mysore sandalwood is creamy and incensey and comforting in is soft-spoken golden glow. / the common spices, herbs, roots, seeds in a shamama attar are cardamom, saffron, clove, mace, nutmeg, cumin, pepper, coriander, fennel, vetiver, costus, ginger, even dried fruits / I do not get the saffron metallic or the cumin sweat I was expecting/ It might seem like a bad thing but the spices here, unlike with a Prin release or Gujarat or Aziyade or so on, seem dead—as in when one talks abouyt dead black pepper: imagine black pepper, ground from peppercorns decades ago, and left to sit out unsealed. /The main vibe of the spices is musty (which again is one of my favorite vibes, so win here) / But if I were to pick out spices I think this is cardamon dominant—indeed, I can get impressions of Memo’s African leather if I open myself in silence and perhaps even more, given the same cardamom and sandalwood and chocolatey leathery oud, to Ormonde Elixir (enough to render the Ormonde Elixir redundant, in fact) / I get nutmeg as well, which boosts that dusty feel

The oud in the base is not cambodian like in ormonde but rather Indian oud: barnyard-leathery, smoky, with a slightly sweet resinous undertone, although here—one could say unfortunately, but not every piece of music needs to be a Coltrone solo—underdosed / the oakmoss, subtle too, add as a mildewy bitterness that help fuzzy the texture and support the vitage feel with the ppeach / Benzoin give a faint vanillic glow to the tarry leathery labdanum / this woody-amber chypre base continues to hum with the ghost of peach and spice, the cocao mainly working with the indian ooud to create a fruity and earthy wood smell /

I feel peach in the immediate drydown more than opening but is perhaps always there—a subtle sweetness—contributing that Rocha’s Femme classic vibe / the antique mustiness is great, so great that now—after exploring several Russian Adam releases, especially the absolutely stunnign War and Peace 3—I do not know if I prefer Bortnikoff and Prin over him: Prin answers my animalic need best but his fragrances, even if not muddy in themselves, get muddy with one another (one-trick Pony style) and as I explore the artisanal space more and more (and experiencing, for example, how Ensar uses ambergris and musk instead of ambroxan and cashmeran and other lab aromachemicals to anchor his compositions) my tolerance for synthetics has decreased (which might, like one of those gushy-rape experiences that leave you wanting the roughest chokes and kidney punches and anal poundings, might have spoiled my love for some of the ones I most held dear); Bortnikoff brings florals and a trained-perfumer feel rare in the artisanal space but his fragrances, with exception to a few, do not answer my animalic itch (not to mention he has clearly went the sellout path of large batches and mass-appeal) /

Overall my exploration of the artisinal space has made me appreciate schooled perfumers who trained under masters: Zarokian, Corticiatto, and so on could run circles around many of these artisanal perfumers—and yet something needs to be said for ingredient qualitu because I keep coming back to Ensar and Areej and the like. / Still, I do fantasize that some of these schooled perfumers had access to some of the stuff even the flakiest northwestern Portlandia hipster artisanal houses have access to /

the overall result is dense but non-gooey dusty antique wood fragrance—the peach and spices and cocoa all recessive in such a way that it seems that Russian Adam was intending to give us a bark accord for some tree in some other planet or dimension / Given Russian Adam’s religion I might even go so far to say that this is the smell of one of the many trees that the Koran and the Sunnah (the sayings of Muhammad) talk about existing in the oud-rich heaven (Jannah) / Russian Adam already has an attar called Tuba, so it cannot be that tree—a tree so enormous that a rider on a swift horse would take one hundred years to travel through its shade without crossing it. / A better candidate, I would say, is the Sidrat al-Muntahā (The Lote Tree of the Utmost Boundary), a lote tree—likely thornless like all the other liote trees in heaven—that marks a border in heaven, a border that only Muhammad can cross and that has leaves like elephant ears and fruits as large as amphoras / This fragrance definitely at least fits the mood of such a tree: ancient, talismanic, fermented—sandalwood plus oud plus moss plus labdanum gives gravitas, like the bark of a tree that spent so much time absorbing the oud-incense of heaven that it seems to look back at you, now with the sexual strength and stamina of 100 men, even as you enjoy your reward of multiple wives, some of which are human and others of which belong to the huris (a celestial species) who will regrow their maidenhood after each bang and thereby disprove Sade’s dictum: “it’s never as good as the first time.”

Now that I have collected all the Areej in the Classic Collection 4, I notice that Ambre de Cocoa has a good deal in common with Antiquity 2 to my nose—a commonality centered around peach and supported by moss and that both have this ethereal duffusion. / The etheral diffusion is a function mainly of ambergris here whereas it is mainly deer musk in Antiquity. / More personally put, the ethereal feel here is more like a jelly-fish throb, a pulsation, whereas there is it more like a constant divine radiance: piiiiiiiinnnnnnnnngg. / There is this otherworthly extraterrestrial-planet chocolate feel in Ambre de Coco whereas a Figment Man soil—largely rooted in a glut of patchouli mixed in with a bit of birch tar—adds a petrichor touch to Antiquity. / Antiquity perhaps pleases me more as a nose diver but Ambre de Cocoa teaches me to let the ethereality comes to me in jelly-fish waves of antique-wood chocolate-peach that just flows around you.

*Fourth stab—I worked mainly on the first half today.

Gordon Ramsay The groomsman—enough of a gravity well as it is (British, tall and blond, famous)—could stand still neither for the vows nor for the life of him. Tweaking his pocket square, his boutonnière, (even licking his thumb to address a cowlick, the best man’s, as the organ unveiled the bride)— his body buzzes “Not good enough!” neuroticism, the amperage: hummingbird. Live-wire fingers wring the back of his neck, bent and rolling its high-stress sinew—bloodless to red to what warrants “Bloody hell!” Caffeinated calf raises as if warming up for the squat rack, crepitus insane against the pregnant pauses of scripture (“Each will be like a hiding place from the wind”), send the eyes of the priest and the groom himself, crossing paths, on a micro hunt: the source clear, clear as raw pork, to the bride’s skeletal “Meemaw” (too severe on manners, too much her own master, too manhandled by the roving fingers of death— infinite in their spare-no-bell-or-whistle foreplay— to succumb to the sorcery of celebrity’s ring), her spine ramrod-straight in the front row. His digits, twitchy as Inuit boarding-school boys in the nastiest dreams of a switch-drunk nun, jazz drum his outseams, thuds of worsted wool signaling (with their broken staccato) for backup. His face, crumpled like a disgruntled gargoyle, churns every which direction downward, sometimes as a wristwatch that is not there— churns yet fails to find final focus beyond the Heraclitean fire, the endless fidget, itself. In the red-herring reprieve of noses blowing, his bleached brows—as if to make the flower girl, mouth open in curiosity over his ways, giggle the spotlight onto her, buying him more time— pump with micro slapstick, their eloquence prelinguistic: “Can you believe they expect us to stand still this damn long? Madness!” Hand gestures of disbelief, curbed mid-flail but still as if to a bad ref call in Game Seven, come complete with thigh slaps and sighs— gusts of agitation. Motor tics upon motor tics mount until the go-to phrases of misdirection (“Oh wow”), the toupees of vocal Tourette’s (“There it is! Unreal!”), find themselves blurted (“Wow. Hell of a point!”) at an edging climax (“Come on now big boy”) where we are called— in a stratagem of complicity-making, sedimented under layers of his muscle memory—to bust out our very own toupee: laughter, its surge meant to soothe our own discomfort as much as his, spin-doctoring the trainwreck of social tension— enough nail-digging cringe to hematoma arms, to tear tights—into something whose normality increases the louder our collective catharsis winds him up into finger-jabbing freedom from the claustrophobia of the bow tie.— “I now pronounce you, husband and wife.”