An Olive Branch to the Cancelers (ROUND 2)

Let's workshop this defense of a restricted-access solution to the art-and-thought censorship--and downright cruelty to artists and thinkers--that has resulted from the excesses of cancel culture.

An Olive Branch to the Cancelers

“human kind / Cannot bear very much reality”—T. S. Eliot

1. Introductory remarks

If we are being fair, the “best” among the cancellers of divergent art and thought—and so not those, the majority perhaps, who merely crave the bacchic rush of collective bullying—do have a point. They have a point, yes, even when they—to art and thought what lynchers are to justice—go so far as to destroy “triggering” artifacts and the people who create or even just discuss them. To be sure, there are those who, to speak by analogy, join the riot only to steal TVs and who kick at the man being group stomped only for a chance to lose themselves in that primeval eros—that “I-did-not-ask-to-be-born-into-this-death-sentence” glee—of ruining the helpless. Push such drunken droves aside, for the time being. Think of those, instead, who riot and kick out of a deep sense of justice, who genuinely believe their torching and trampling champions a heartrending cause.

It might seem bewildering (to a dwindling few) how anyone, even if well-intentioned, could ever feel compelled by justice to censor, silence, and shame artists or to blacklist certain sorts of art and discourse. But just look around. The stark reality throbs. Today it is popular, downright fashionable, to cancel artists and thinkers (especially if they have the “incorrect” optics and affiliations) for painting certain vulnerable demographics—the “good ones”—without idealistic gloss, or for using words they might find “triggering.” Even art caretakers (tasked with safekeeping art, and so definitely not with melting statues down to be “remade with diverse hands”) have become art commissars (tasked with making sure art signals the “right” attitude). It is a time, yes, when museum curators (from the Latin “curare,” which means “to watch over and care for”) would commission—for a social-media spectacle of “racial reckoning”—local children of Wakanda hue to “go wild” with brushes laden with Kilz Premium Primer over the black slaves depicted in a small corner of a mural: an egregious piece of “nonconsensual art” painted by “just another dead white scumbag with a third cousin implicated in colonialism.” These cancelers really feel they are doing God’s work with all their shouting down and doxing and threatening and career destroying. Such cancelers often feel that victimized groups are so in need of protection from unsettling art and ideas (and even from certain typographical squiggles and phonetic vibrations) that any length of cruelty against creators is justified. Any length is justified—public reprimands, entrapments, online exposés, threats, beatdowns, CPS reporting, sabotaging orchestrations—even though such cruelty, almost as if it were part of an insidious agenda all along, amounts to cruelty to the victimized groups themselves. It insinuates and perpetuates the notion, after all, that those groups are too precious to be treated with anything but kid gloves—a demeaning practice that, once normalized culturally and institutionally, further hobbles those groups.

Bewildering as it might seem, then—yes: it is not uncommon in the contemporary western world for people to feel that it is a matter of justice to place gag orders on artists and thinkers, to melt their statues and burn their books. But feeling is one thing and truth—that is, whether that feeling really does align with justice—is another. However much they are readily equated in our decadent epoch, objective truth and personal truth (“my truth,” to use that fashionable cudgel of a slogan) are different. And in the specific cases suggested above, where we deplatform and fire a white professor because he has a character in his poem that uses the word “nigger” or depicts a paraplegic getting gang raped, or where he voices worry about the growing—and perhaps homophobic—normalization (and cash-cow encouragement) of children being put on puberty blockers and undergoing sex-reassignment surgery, it does seem that the banning—let alone the communal frenzy of cruel crucifixions—cannot really be justified. If we zoom out a bit and speak more generally, however, the impulse to suppress unsettling expressions—perhaps even to boot-neck and lynch-mob extremes of bitter vengeance—is not so ridiculous as it might seem.

In the following I hope to show precisely that. In particular, I hope to highlight the dangers that artists and thinkers do pose to the human soul and to the very fabric of society (section 2), dangers that remain even when whittled down by the solid reasons for thinking they are overblown (section 3). In the end, I propose a restricted-access solution—one, admittedly, born of frustration and that borders on satire—that respects both the crucial value of art and thought, on the one hand, and the dangers of art and thought, on the other (section 4). My goal, at minimum, is to spur discussion on how to preserve—and even how to encourage—celebration of art and thought while minimizing their capacity for harm. The path forward requires nuance. Easy answers are rare when core principles collide.

2. Empathy for those cancelers who think that artists and thinkers are dangerous

There are genuine risks in allowing artists to hold up a mirror to who we are (as artists do). What shadows, what futures, might take shape? There are genuine risks in allowing thinkers to machete through the jungles of the unknown in search of truth (as thinkers do). What vipers, what spiders, might they provoke? Think about it. How could artists and thinkers—these weirdo explorers, these illusion dismantlers, these taboo challengers—not pose a threat to us, our DNA almost ninety-nine percent identical to our tree-swinging siblings? How could there not be dangers especially for the western youth, coddled in inbred cyber bubbles of likeminded avatars and where the algorithm feeds them only what it knows they like? In fighting against the cancelation ethos, we might be inclined to insist that the dangers are overblown by the cancelers—overblown to justify their mobbish rage. Despite the great temptation, however, my intellectual conscience does not allow me to downplay the threat.

Heterodox expression can stir crises of heart and mind, quaking our sense of identity and belonging (leaving us unmoored). Repercussions ripple into the distance. The pictures artists render, the territories thinkers traverse, are so often not for the faint of heart (particularly if that heart cohabitates with an open mind). Even mortal wounds can fester quietly, cracking spirits years later. For the same reason the university—especially if healthy, and so a bastion of viewpoint diversity—is not suited for everyone, exposure to certain artworks and thoughts is not either. Can we reasonably expect the masses to handle even artworks and thoughts that pierce, beyond our protective atmospheres of delusion and puerile cope, right into unconscious abysses and existential voids? Of course not. We shelter our children for good reason.

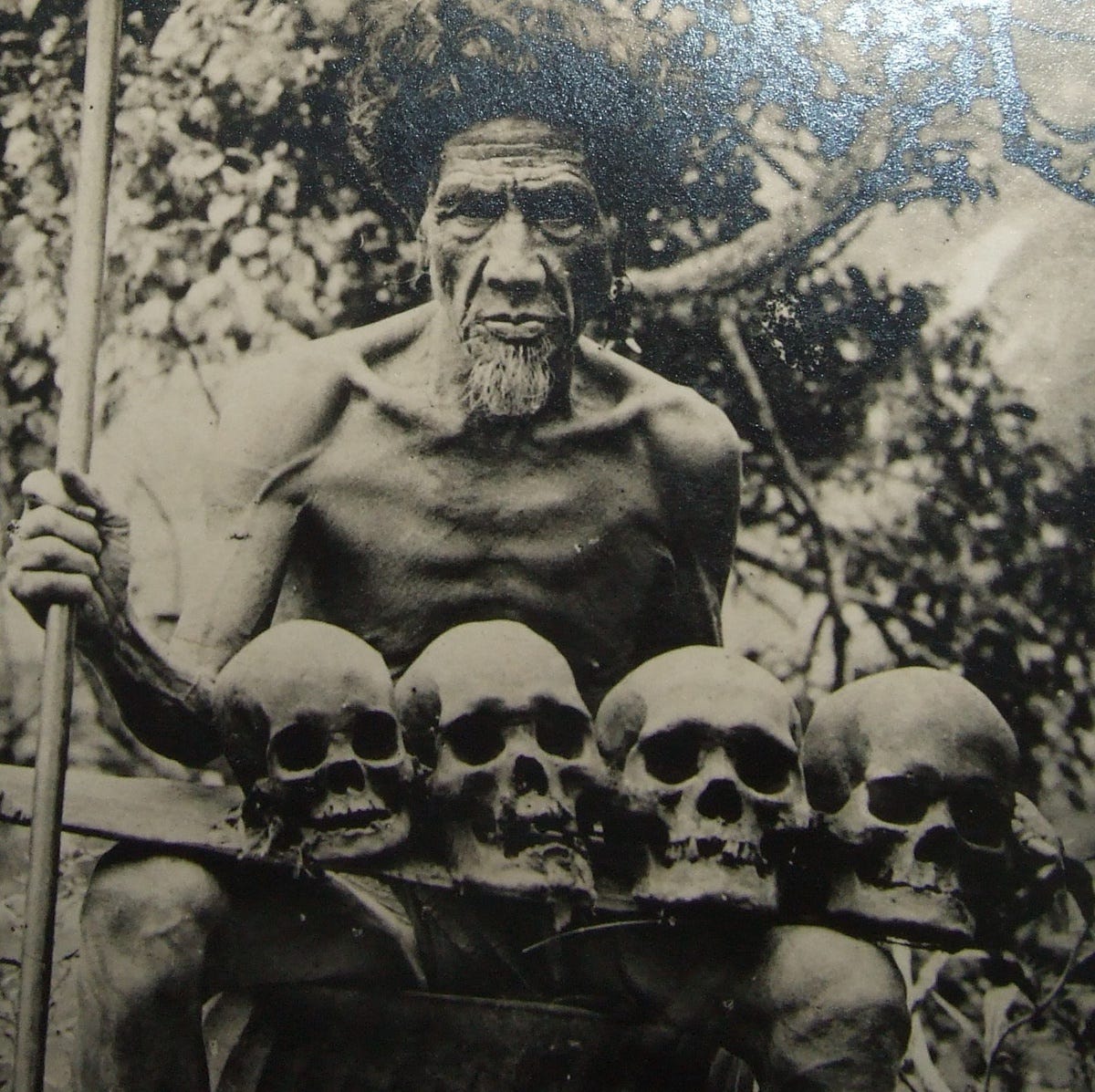

Those of us who have felt the wrath of the triggered cancelers might be inclined, in understandable backlash, to scream “Get a fucking helmet, you little Nancy Reagan cunts!” But even those who say—much more moderately, in the placating tones of baby talk—that “Dostoyevsky and Shakespeare, disconcerting as they can be, are good for you like exercise” underestimate the power of expression to wreck people, to leave them reeling in vertiginous anxiety and suicidal depression. Nietzsche did say “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” But as with much of what he says, he did not think this applied universally. He spoke at length of how dangerous, how unhygienic, how life-shattering, it could be for certain people to be exposed to certain art and thought. I have followed Nietzsche on this before. (A decade back, one of my Stan stalkers blamed my skeptical stance on the possibility of moral responsibility for his descent into a bed-ridden depression whose rock-bottom was job loss, divorce, and a box-cutter poised against a jugular pulsing in the bathroom mirror. The obsessive cretin—activated to apoplectic extremes by my years of not responding to his “I’ll-rape-your-kid-for-what-you-have-done” emails—sought retribution for my “corrosive philosophy” by harassing my family on Facebook. My uncle, trying to mitigate the situation, eventually responded to the daily barrage of DMs about how much of a “piece of scum” I am with: “It’s just a damn philosophy paper! Jeez.” However sweet his intentions, I did not agree with that response. As I told my uncle on the phone, it underplayed the life-altering impact—and potential devastation—of my arguments.) I continue to follow Nietzsche on this matter too—or at least I am willing to as a conciliatory gesture to the metastasizing cohort of cancelers. Because if Nietzsche is wrong, I fear that the pendulum of justice might swing—if we really think about it—the opposite direction: where it would be a matter of justice to show no tolerance whatsoever for canceler impulses (and perhaps, although only perhaps, to torture some of them if only—like skulls on a pike—as a deterrent for anyone who might be thinking about walking the path of cancelation).

Aside from just drowning out the call from deep within me to go headhunting (like so many of my indigenous brothers from another time and place), there is good reason to follow Nietzsche on this. Most of us would double over if they really tried to digest what goes on in Shakespeare and Dostoyevsky. Most of us are understandably desperate to keep out of mind how much ammonia-scented suffering—intense, grotesque, drawn out—plumes from the factory farms on which we suckle. Most of us would falter, give up, if we were to face our true situation and its the Mandelbrot set of disturbing realities:

how vast the universe extends into the micro and out to the macro;

how much our happiness (as beings with nice shoes and phones and toilet paper and fast food) relies on death and slave labor and other forms of cruel exploitation;

how many of our most cherished taboos—say, sex between man and okay-to-proceed-signaling horse or between woman and the erect-and-pursuing dolphin—are as unfounded as yesterday’s taboos against homosexuality and interracial marriage;

how the microbes in our bodies, which outnumber our own cells by far, shape our cravings and our moods (our very identities even);

how we will be forgotten just as thoroughly as our ancestors ten generations back, just as thoroughly as one day the entire human species;

how there is a continuum between molecules and humans (such that we are not different in kind from the rest of the beings in the universe);

how there are thousands of deaths a year merely due to medical error;

how the historical figures we revere, including Jesus, committed unsavory actions (the least of which was eating living flesh in the blind drive to live on top of masturbating, perhaps even with sheep in mind, in the blind drive for pleasure);

how there are black holes ripping apart entire galaxies right now (just as there are thousands dying in myriad agonies over the course of one day here on Earth);

how we breathe in pounds of dead skin from other humans over our lifetimes;

how animals (think of the dolphin in the vertiginous blue), including even the pets we adore (think of our dog at home while we are at work), experience mental and physical and perhaps even existential suffering we may never fully comprehend;

how a clot can kick free at any moment and end all our plans (the showerhead flow breaking into discrete drops the last thing we ever see);

how a blow to the right hemisphere can make us think we are dead, or that our left side is made of wood, to such an extent that we slit our own wrist for nonbelievers to witness the lack of blood;

how it is statistical likely that we will experience deep loneliness in our old age, however rich our current social connections stand;

how many infants, some of whom pimped out by their own druggie parents, have been gangbanged to death under the groans of “Ooh yeah baby” and “Little bitch loves it deep”;

how our memories are fallible, reconstructed every time we recall them (which makes them susceptible to distortions and alterations and outside suggestions);

how all our behaviors and thoughts and feelings are no more ultimately up to any of us than the rolling of a rock is ultimately up to that rock (one of Nietzsche’s most dangerous of his “dangerous truths”);

how there are brain eating amoebas in popular swim holes, one to which kids are particularly susceptible (given how in unfamiliarity with the medium are more prone to take water into the nose);

how the sky-father God is just another Santa-Zeus;

how we might be nothing but, or at least largely, chemical bags—or, better, chemical flows, processes, that our left hemispheres have us congeal under the stability-suggesting term “bags”—of senseless and stasisless particles interacting according to cold laws of physics;

how so many torture devices have been used throughout history to inflict suffering and extract confessions (the rack, a device where ropes around the ankles and wrists slowly tears the limbs from the body, or the iron maiden, a metal chamber filled with spikes that would impale the person when shut inside, or the pear of anguish, a metal device that was inserted inside vaginas and mouths and anuses that kept expanding in girth by turning a screw, the brazen bull, a hollow brass statue of a bull with a fire underneath that would pressure-cook those placed inside, or the heretic’s fork, a metal piece with two opposed bi-pronged forks—one under the chin and the other against the sternum—ensuring the person could not sleep or lower their head for days);

how we are born alone astride the grave, those who are merely twenty merely having weekends left numbering merely in the two thousands.

Given this iceberg-tip of unsettling truths, cancelers of the unsettling do seem to have a point. They especially have a point when we also consider the moving mastery with which geniuses like Schopenhauer have been able to nail these truths into the core of our souls.

But wait, there is more (as Ron Popeil would say). Most of us shudder to behold what we see within the mirrors artists and thinkers would have us confront. The reflections staring back are often base-goaled (if goaled at all), inconsistent, power-hungry liars and cheaters who have done—just like the Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. and various other people we venerate as saints—so many ugly things:

bullying the classmate with Down syndrome;

punching the baby (“That little nigga ain’t my kid!”);

breaking the dog’s ribs with a steel-toe kick;

jerking off into the panties of our own mothers and sisters;

dumping the body even of Leibniz in an unmarked grave as if he were not one of the greatest pinnacles of our kind;

devouring plants (plants that, unable to flee, guard their lives with thorns, bark, caffeine; plants that even scream when cut), devouring even their sexual parts and yet while we find it unethical to rob bees and cows of honey and milk, the only two murder-free foods;

gas-chambering whole ethnicities after starving and raping them, after running experiments on them, after forcing them to pick which of their children will get its head knifed off (yes, by the chooser himself);

fantasizing about suicide as a last-ditch effort to harm our loved ones;

hurting (banishing, silencing, shaming, mauling) the weird (as we especially like to do in mobs) ultimately because we have been forced to suffer and then die in a microplastic-schizophrenia-tornado-flood-Ebola-retardation-supernova reality we did not ask to join.

(And we might extend even more empathy when it comes to those who go so far as to shatter the mirrors. We all know, to speak by analogy, the trope, after all, that the biggest ragers against homosexuality—especially those willing to protest homosexual depictions in art and even to kill homosexuals—have some meth-fueled things in their own closets!)

Especially for people swathed by thicker-than-usual atmospheres of ignorance and wishful thinking, especially for people who need to huddle away from the truth just as much as they need to huddle into the infantile rhythms and all-too-chimp content of pop music, especially for people who lack the root depth and strength to stand even mild winds blowing against their favorite notions, artists and thinkers really are live grenades. Artists and thinkers so often shine a merciless light on what “nature has seen fit” to hide from us (the blood pounding, for example, relentlessly through our vulnerable bodies), on what might not be in the interests of many of us to see (the microscopic mites, for example, in fervent mating dances all over your face), on what might not be hygienic for being our best selves to know (that your thoughts and counter-thoughts and intentions and counter-intentions, for example, simply just appear in a steady flow rather than as a result of your choosing that they appear). They so often shake capsize our cherished beliefs and quake our identities (giving us reasons for thinking, for example, that Jesus is not Lord of the reality where ninety-nine point nine percent of all species that have lived on Earth are now extinct). They so often make society hesitate (giving us reasons for thinking, for example, that those we are at war with are humans with dreams and families just like us). They so often endanger what we value (giving us reasons for thinking, for example, that no one is morally responsible and, thereby, that retributive rewards and punishments are uncalled for). They can make us second guess ourselves, even in situations calling for decisive action. They can undercut our feelings of security. They can inspire us to indulge, through empathizing with certain characters, in unhealthy feelings like rage and jealousy. They can challenge our feelings of specialness, our feelings of having more than mere instrumental value. They can legitimize or even glamorize base lifestyles of murder and rape and drug use (rather than of philosophical contemplation and temperance and good deeds). They can make us wonder—in the face, say, of the seemingly looming heat death of a universe—“Why bother?” They can demoralize us, even when they speak on the redeeming aspects of life, merely because their abilities seem so out of reach—as in when Diderot said “When one compares the talents one has with those of a Leibniz, one is tempted to throw away one's books and go die quietly in the dark of some forgotten corner.”

3. Empathy for those free-expression advocates who think the dangers of artists and thinkers are overblown

So I have shown that the urge to cancel is not so unreasonable as it might seem (as it might seem especially to those who have felt the mob wrath and have known the damage done by recent university purges of heterodoxy that make the red-scare purges look like a joke). To be sure, and as those who like to say “Just get a fucking helmet” might want to put on the table: just as we perhaps should not underestimate the power of artists and thinkers to ruin people who cannot digest their expressions, we should not underestimate the immune systems of those who cannot digest their expressions. Those worker ants, those bronze souls (as Plato might put it), who are not equipped to travel with artists and thinkers into brutal realities have an inherent resilience, eons old, protecting them against anything that might be too harsh for their psyche. Just as the body shelters humans from extreme pain, it has mechanisms to keep delusions intact against some of the blackest insights and arguments.

I want to devote some time to showing this resilience in action. Worker ants have robust immune systems, sometimes too robust for their own good (as in when its banning of contagion is so thorough that they become decadent). These immune systems have countless ways to keep out the foreign. Worker ants ignore deep art and deep thought. That is the chief strategy. They straight up ignore it, and often enough build a culture attitude—an attitude that becomes a source of pride and identity (as much as their alliance with certain football teams)—that such art and thought deserves ridicule. We see this in the trope of mocking and bullying the nerd. And even when bronze souls hang art up in their homes, they do not tarry before it. It does not bring them to tears. Hit with a proof that would undermine their hope and purpose, their defense mechanism kicks in: “That’s just your opinion!” They deflect. They cancel people for heterodoxy. They mock people for being different—unless, of course, that difference is within their sanctioned norms. Their circular reasoning often lacks critical introspection: “Of course the bible is the literal word of God: the bible says just that!” They are slippery. They use all sorts of cheap tricks, however irrelevant, to avoid letting in anything unsettling. Any irrelevant reason will do: “Why would I trust him? He was canceled”—yes, canceled for something totally unrelated to the issue at hand. “Why would I listen to her? She’s on the other side.” They often weaponize identity: “You don’t get to say anything to me since you are x,” where x is so often an identity group outside the identity group they have convinced themselves with full righteousness has a monopoly on speaking the truth. Whataboutism is one of their cardinal maneuvers in their rhetorical repertoire: “You make the racist claim that there is a problem with violence in urban black communities? Huh? What about all the white school shooters?” They cloak themselves in selective skepticism, conveniently disregarding when it contradicts their cherished beliefs. “How do I know these statistics aren’t made up? Oh, and look, this one is funded by a religious think tank!” They throw challenges they know can't be definitively met: “Okay Dr. Scientist. Prove to me, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that this supernatural phenomenon isn't real. Until then, my belief stands!" Trick upon cheap trick—that is their game. They say “No black person will deny that white supremacy is baked into the institutions of this country. Driving down the highway, walking into stores, they move in constant fear.” And when you say “I’m black and yet I do deny that!” they double-down with the No-True-Scotsman maneuver: “No true black person, a black person that lives an authentic black experience, will deny that, though.” They are evading little cretins: “You go on and on about how I shouldn’t smoke, but you used to smoke." They will wear you down with obstinacy, especially if you do not suffer fools wisely: “Bestiality has always been forbidden—that is why it should stay that way." They are elusive little eels. They run out the clock with wave upon wave of immune cells prepared to do any maneuver (rhetorical or physical) to block out all contagion. And these are the most redeemable of them, a relative rarity compared those whose stunted brainpowers limit them to no more than that one nauseating trick now institutionally emboldened even on campuses: the heckler’s veto.

We observe this pattern vividly in the following conversation, where Person B repeatedly employs rhetorical strategies of evasion that prevents Person A from gaining much of any traction. One wonders how Shakespeare could ever ruin someone like Person B.

A: “So yeah, that’s why I think we should provide healthcare for all citizens."

B: “But universal healthcare wouldn't work here: our country isn't suited for it [(Circular Reasoning)]. Besides, I think it’s disgusting for doctors to work basically for free [(Strawman Fallacy)]. The quality of care would suffer. Think of the children [(Appeal to Emotion)]!"

A: “No, the government would pay the doctors in accordance with their value to the society.”

B: “You want to hike up my taxes to pay for everyone else's healthcare [(Strawman Fallacy)]. I heard it all before [(Dismissal by Familiarity)]. It is too much of a burden as it is. You yourself were, ten minutes ago, were grumbling about taxes [(Tu Quoque)]!"

A: “Many countries provide universal healthcare without overburdening their citizens with taxes. Perhaps it would be a matter of lowering taxes in other areas."

B: “So you think we should be like other countries [(Strawman Fallacy)]? Trying to turn us communist. I figured that. You keep spouting that nonsense around here and get your ass beat [(Appeal to Force)]. Do you know all the bloodshed that came from communism [(Appeal to Emotion)]? Do you know all the bloodshed, in my own family, that came from fighting that disgusting system [(Appeal to Emotion)]?"

A: “Many capitalist nations successfully implement universal healthcare."

B: “But do they have the same quality of healthcare as we do? I think not. Show me the evidence."

A: “Well, I obviously can’t present all the evidence here. I don’t have the WHO statistics in my damn head.”

B: “See, I didn’t think you could! Name one damn country.”

A: Well, Germany. Germany has one of the oldest universal healthcare systems. The quality of healthcare there is superior according to the WHO.”

B: “Germany!? The birthplace of Nazi Party [(Red Herring)]. Of course, you would go there [(Personal Attack)]. Why would we trust anything they do [(Genetic Fallacy)]? Why would we trust anything the WHO says for that matter [(Genetic Fallacy)]? Do you remember how they handled the COVID pandemic [(Red Herring)]? Besides, most of those countries aren't as diverse and as large as ours. It wouldn't work here [(Special Pleading)]. So you’re gonna need to name a lot more countries than just one [(Moving the Goalpost)]."

A: “It works pretty well in Canada.”

B: “Canada is right on the verge of going socialist. Everyone has to wait months before a checkup while the cancer spreads [(Exaggeration)]”

A: “That does not seem to be very accurate. No system is without its challenges. But these seem overblown. You don’t literally mean what you said, right?”

B: Actually, I do. I know people in Canada [(Anecdotal Evidence)]. But let’s not get sidetracked from the bigger issues. Say we implement universal healthcare here. Not only would that go against our traditional values [(Appeal to Tradition)], but what next? Free houses and cars for everyone? Where does it stop [(Slippery Slope Fallacy)]? Besides, most people I know think universal healthcare is a bad idea [(Appeal to Popularity)]. You are that full of yourself that you are really going to suggest to me that they all wrong [(Personal Attack)]?”

A: “Providing free healthcare has no link to providing free cars. And just because many people believe something doesn’t mean it is true.”

B: “But these are Americans who believe it [(Appeal to Popularity, Patriotic Angle)].”

A: “I’m American.”

B: “I’m talking true Americans [(No True Scotsman Fallacy)]. And let’s not get into that. Really, universal healthcare can mean a lot of things to different people [(Appeal to Ambiguity)].”

A: “It can differ in the details (particularly the details of implementation). But the general idea is pretty uncontroversial.

B: “You say that, yeah. But how can I trust you? You are on the other side [(Circumstantial Personal Attack)]. I have better things to do than to engage in these abstract discussions about what is the correct definition of universal healthcare and all that [(Dismissal by Unworthiness)]. These conversations don’t do anything anyway [(Dismissal by Pointlessness)]. I have to pick up my kids [(Exit Strategy)].”

A: “I will say though that it is kind of ridiculous to say that you can’t trust me because I’m on the other side.”

B: “You calling me ridiculous [(Strawman Fallacy)]? And didn’t I just fucking say I have to go!? You trying to stop me from picking up my kid? I will fuck anyone up who does anything to put my kid in danger [(Appeal to Force)].

As should be clear, Person B employs an almost impenetrable wall of rhetoric that allows him never to be shaken in his worldview, never to feel the impact of contagion. This pattern of evasion is found across the political and cultural spectrums. I bring it up to demonstrate the power of our psychological survival mechanisms, which surely can block out so much of dangers posed by philosophy and science and art.

4. Solution: restrict not the artists and thinkers but the people from accessing them

I do agree, then, that those who would otherwise be destroyed by artists who reveal how gruesome humans can be or by philosophers giving proofs for how nothing is ultimately up to any of us or to physicists explaining how vast the distance between stars are and the like have the immune systems (the cultural attitudes and chimpish rhetorical maneuvers) to avoid feeling the sting of dangerous ideas—something Nietzsche did not emphasize when he spoke of the dangers of exposing the everyman to certain ideas. That said, surely it is safe to say that there are exceptions—that there are people, that is, who cannot digest the dangerous truths of artists and yet whose immune systems are too feeble to keep out these dangerous truths. Indeed, some artists and thinkers are talented enough to slip in, under the guise of seemingly innocuous jokes or fairytales or so on, what would be even to bronze souls with excellent immune systems ruinous black. Yes, thinkers and artists have their rhetorical maneuvers too, such that years later after exposure bronze souls find themselves unable to get out of bed. In the very least, then, the urge to cancel heterodox and scary ideas is still reasonable.

Do not get things confused. However much empathy I have for the canceling ethos, I do not think we should cancel—ruin, render unemployable—artists and thinkers who unsettle us. Nor do I think that their work—red pills, even black pills, for many of us—needs to be destroyed. Indeed, I feel that artists and thinkers should always be cherished.

One might wonder how I can square these points with all that I have said to show how reasonable the canceling ethos is. There is a way to honor the good reasons behind the growing attacks against free expression while at the same time honoring unfettered free expression. Artists and thinkers should not be blocked from creating. If there is going to be any blocking, the people should be blocked from receiving! Put a rag over the eyes of the people, not over the mouth of artists and thinkers. In a phrase: block the people, not the creators.

What people? People who lack the requisite mettle for openness (especially if they also happen to be backwards burners of whatever they find—according to the quirks of their subjectivity, and on the grounds that safety trumps truth—unsettling or, worse, whatever others have told them to find unsettling). People who lack the requisite critical acumen (especially if their idea of justice is forming mobs to lynch and shame and ruin whatever interferes with their precious beliefs and made-for-TV-Christmas-special security). The college course or the book should not be forced to go away because people are offended. Rather those people should be forced to go away. The lynchers among them especially need to be blocked out and encouraged instead to go somewhere (like to therapy or at least outside their own cyber bubbles) to build up their respect and stomach for truth and beauty. Especially if they want to act like kids, they get treated like kids. That is the idea.

So that they can no longer be disrespected, be tarnished, by those—whether innocent or gremlin—too moronic to grasp context, or too set on a safe-space agendas to allow true diversity, or too riddled with PTSD to welcome anything unsettling, or whatever, lock the artifacts of human creativity away for the select worthy. Lock them away especially for those who, instead of having a panic attack just by gazing up at the stars, feel at home considering the scariest truths of psychology and physics and philosophy. Lock them away especially for those who, instead of bleeding to death from small scratches, can assimilate tragic accidents and awareness of their own cruelties into their projects of empowerment. Better to have the insights of artists and thinkers—yes, even when those insights center around how to spread misinformation or make bombs and bioweapons—at least safeguarded away (perhaps for later use by the courageous and wise) than to destroy those insights in fear of the damage it could do. That is the idea.

We should celebrate the great works: Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun and Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Caravaggio’s “Judith Beheading Holofernes” and Munch’s “The Death of Marat II,” Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” and Coltrane’s “Favorite Things,” Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature and Greene’s The Elegant Universe, Attell’s “Skanks for the Memories” and Gervais’s “Humanity.” We should speak about the great works with reverence and yet only let people access them after they have been vetted, tested. Perhaps we should develop ceremonies around the creations that regulars—the bronze souls—cannot access, public praise of the wisdom of texts and public praise for the select allowed to read them. These ceremonies might involve the history of the horrors that befell civilization when the regulars started burning texts and firing teachers who taught them, who started cracking down on free expression even in universities, in the name of ensuring safe spaces. We might inject stomach-toughening therapy in early education for the sake of equality of opportunity. And we might institute consequences for anyone who would burn paintings and books and so on (like having them paint or write essays).

A barrier of licensure, a rite of passage, to prove one can handle potentially triggering discussions and diversity (real diversity, not the mockery of diversity that we see from diversity initiatives that hear tales of “viewpoint diversity” as Nazi dog whistles)—at least some sort of barrier (a testwall modeled on the paywall) should be established to protect poems and their poets, paintings and their painters, theories and their theorizers. There is a pragmatic effect to this. Watch how the respect for art and thinking increases! Just as men have to prove themselves worthy—have to be vetted and tested—to gain access to a mate, audiences have to prove themselves worthy—have to be vetted and tested—to gain access to the products of creative energy. Just as women who respect themselves enough not to take shit from men result in men shaping up (if only faking it until they make it), art that respects itself will have us all shape up, such that even people who are not just faking about being helplessly triggered by books and paintings would be less inclined to speak out (let alone to trash such artifacts and the people associated with them) for fear of showing that they are not worthy. We all know the forbidden-fruit effect!

Mistakenly blocking ten people from reading a book is better than burning a book. Let the people have their coloring books while the select read Faust, which at least could be said—at least as a dramatic countermeasure to the disrespect for art and thought by those too sensitive to participate—to be worth more than a thousand ordinary lives. Let the people have their pop (but perhaps a case can be made that even they might need to earn the right to that too if it would prove too dangerous to such a social arrangement) while the select behold sculptures too hurtful or disruptive for the others.

5. Concluding clarifications

So there goes my gatekeeping solution to the problem of how to respect the fact that art and thought are both dangerous and yet highly valuable. My remarks, which inverts the conventional perspective that genius must prove their worthiness to the masses, are born of frustration at the widespread infringement of free expression and all the cruelties of cancel culture. Cutting through all the satire, I do think that cultivating emotional resilience is the way to go. In effect, I align more with those who say “Get a damn helmet” than I suggest in the essay. I believe that exposure to new ideas, even difficult ones, can help people grow mentally and emotionally. I believe that avoiding the scary and challenging stunts development. People should be education about the importance of critical thinking, debate, and the value of diverse viewpoints. That does not mean that my empathy for the cancelers is a lie: it is important, at least for most people, to have atmospheric buffer of delusion against the void—something that art and thought could strip away (especially in high doses).

It is important to notice the key qualification in the essay: if—if—there is to be any restriction, then it should not be on artists and thinkers from creating but on people from accessing their creations. I do stand by that. Restricting access to consumers as opposed to silencing, let along ruining, creators is far less problematic from a free-speech perspective. If anything, it is not the artists and thinkers who must prove themselves worthy of standing in the light of audiences but rather audiences who must prove themselves worthy of standing in the light of artists and thinkers. This especially needs to be said, insisted upon, in our era where bitch-ass education and communications majors can act like they are better than the geniuses of mankind, banning their masterworks because they have, for example, tenuous ties to colonialism.

Understand, though, that I personally lean pretty strongly away from restriction. I believe open discourse and the cultivation of critical thinking is ideal. The access-restriction idea is not necessarily an ideal in itself. It is a tactical response meant to counter all the censorship and ruin of livelihoods and disrespect for truth—all the canceling based on disingenuous claims of being triggered. I do not want to overstate the point, however. It is hard for me, I do admit, to get clear on how seriously I take this proposal. My frustration, and negative experiences with cancel culture, might be clouding my better judgment. That said, I do have political leanings away from democracy and toward noocracy. I am not much moved, then, by the main worry that someone might voice to my proposal: namely, that my solution invites elitism. Who decides who gets access? Who makes the tests? Those with the stomachs for staring into voids, of course: the Nietzsches of the world—the philosopher kings. The concentration of power over information might seem concerning. But if—if—there is going to be any restriction of information we want that restriction to be in the hands of the tough brains (just as we would want the navigation of the ship to be in the hands of the expert captain, as opposed to the mere oarsmen, if there is going to be any navigation of the ship).

Yes, it is difficult to determine precisely who is vulnerable to harm from exposure to which ideas. One might wonder about the potential for overly-broad restrictions if we take my satirical solution seriously. But again, mistakenly blocking ten people from reading a book is better than burning a book. I do stand by that. I stand by that even outside of satire. If there is going to be any blocking (which, remember, is only and “if”), then yeah: block not the creators but the little cunts who are getting everyone fired, who are censoring, silencing, and shaming creators for being too “triggering.”

Yes, there might be better ways to prepare people to handle complex ideas: education and guidance, rather than restriction. Better tactics may exist for undermining moral panic claims: like counter speech, open debate, and cultivating emotional resilience. Three things need to be said, however.

(1) My approach in the essay does not preclude using education and guidance along with restriction. Indeed, I mention therapy. If there is a “testwall” to access, surely that suggest that there will be institutions built around getting people ready to pass that test.

(2) In our historical moment, when people are censoring art and getting professors fired and banning books, restriction would seem called for if—remember, if—any restriction is called for.

(3) Perhaps we ought to consider my gatekeeping solution, which involves proving one’s worthiness to stand before the fruit of a Goethe, a temporary emergency measure (like affirmative action or like opiates to blunt the pain of acute trauma). While we are in the temporary period of blocking the gremlins from clawing everything to pieces, we can start really tripling down on our education efforts and building up our rehabilitation and counseling systems. Just as we work on changing the cultural attitudes of black people in that narrow band of time when we are using the syphon of affirmative action to get them into sectors where they have been historically blocked (so that when we stop sucking the hose black people are still entering these sectors all on their own), we work on changing the cultural attitudes of these gremlins who would burn Faust and mock Goethe—work on showing them the horrors of their cancelation agenda and, especially for those rare few who really are triggered, building up their mental and emotional and philosophical resilience.

Yes, some exposure to new ideas, even difficult ones, can help people grow in toughness (especially if done gradually). And yes, blocking out all challenges impedes growth. But these points are easy to voice when we ignore the terror imposed by little university punk students: the lives of so many professors ruined on grounds that these students are triggered by discussions and ideas and words (especially from people with certain optics: white male optics, let us not beat around the bush). A lot of that is largely performative. One way to respond to that performance is to call it out for being performative. People like John McWhorter take that approach. When I am being sober and straightforward, that is my approach. But another approach, one that meets their manipulation with manipulation, is to take their tantrums seriously (even though we know those tantrums are not really serious) and ban their asses instead of that art and thought that supposedly “does violence” to them. Restricting them from accessing what they find so triggering, you see, serves as a clever punishment for their lying about being triggered and for all the havoc that has come from that lie. If they cannot handle triggering ideas, ban them from university instead of banning readings and professors. That is the idea.

Yes, there are plenty of dangerous ideas already out there, in which case limiting exposure of vulnerable populations may be unrealistic. Two things here. (1) The fact of being blocked has symbolic oomph, even if it is not really protecting people. (2) The fact that our linked-in culture is already rife with triggering things, things way more triggering than the books and creators these bullies lash out at, only further suggests how much the complaining and canceling is as performative tantrum to exert power over people (professors, poets, scientists, and so on). Many of these bullies grew up on Pornhub and actively use it. Many of them have grown up on what they still sing in the shower: music filled with the word “nigga” that they suddenly cannot stand to hear in class. Hmm. Yeah right. I have their number!

Do you see, then, how the response I flesh out in the essay has rhetorical power? To stop their gremlin onslaught it can be effective, as anyone who is a parent well knows, to take seriously their manipulative lies about how devastating it is for them to hear certain words or read certain statistics or see certain images. “Oh, so you’re really triggered? Okay then. We’re going to block you from accessing scary stuff. No, no, no. We’re not going to fire the bad professor or ban that bad book, Sweetie. We’re going to keep you sheltered. No—no more scary movies until you show Mommy and Daddy that you can handle it. Okay? Now eat your din din.”

You see the rhetorical jujitsu of this? It functions primarily to flip the script on performative outrage, meeting manipulation with manipulation to expose it. And since these restrictions would affect even those who would never think of participating in canceling, it has additional power. It is like the idea of no longer allowing the fifth graders to eat outside because a minority of them have been fist fighting on the playground. Punishing everyone for the mistakes of a few—an old military strategy.