A Case for Hard Determinism

Let us workshop this essay in defense of Hard Determinism, the view that (a) determinism is true and that (b) human free will is incompatible with determinism. (Dedicated to my cousin Randy, RIP.)

A Case for Hard Determinism

Dedicated to my cousin, Randy (RIP)

1. Introductory Remarks

The classic doctrine according to which humans lack moral freedom, the sort of freedom required for moral responsibility, is Hard Determinism (HD). HD claims that at least some form of Determinism incompatible with human moral freedom is true. HD, in other words, consists of two views: (1) that some form of Determinism is true and (2) that human moral freedom (human free will) is ruled out by the form of Determinism in question.

The burden of proof seems to fall on advocates of HD, rejecting as they do some rather basic intuitions. Most of us cannot help but believe, after all, that at least sometimes we act freely, that at least sometimes what we do is genuinely up to us—up to us, that is, by not being entirely a function of factors beyond our ultimate control. Most of us cannot help but believe, relatedly, that at least sometimes we can be morally responsible, that at least sometimes we can be genuinely deserving of praise or blame—deserving of praise or blame, that is, for the sake of justice rather than merely for the sake of pragmatic consequences (such as to protect society or to shape future behavior). HD, however, rejects both of these cherished beliefs.

Consider the following two arguments for HD. These arguments correspond to the two most invasive and comprehensive forms of determinism: Chronological Determinism, the view that all of what is going on at any point in time settles or fixes all of what comes next, and Absolute Necessitarianism, the view that things could be no other way than how they show themselves to be since they are necessitated ultimately by what is self-necessitated (if they are not self-necessitated themselves).

HCD Argument

1. Chronological Determinism is true. (Determinist Premise)

2. If Chronological Determinism is true, then humans lack moral freedom. (Incompatibilist Premise)

Therefore, humans lack moral freedom.

HAN Argument

1. Absolute Necessitarianism is true. (Determinist Premise)

2. If Absolute Necessitarianism is true, then humans lack moral freedom. (Incompatibilist Premise)

Therefore, humans lack moral freedom.

These arguments are obviously valid, which means it is logically impossible for their conclusions to be false on the assumption that the premises are true. In order to defend HD, then, I need to defend both premises of each argument. That is what I will do in this post, which draws upon my paper “A Rationalist Defense of Determinism” (and, to a lesser extent, “A Cosmo-Ontological Case for God”).

2. Why the Determinist Premises are True

In earlier posts I have defended both Chronological Determinism (premise one of the HCD Argument) and Absolute Necessitarianism (premise one of the HAN Argument). You should perhaps revisit those posts before proceeding. For at least a refresher, however, I will give a quick defense of these positions.

Chronological Determinism, which is the form of Determinism that contemporary metaphysicians typically have in mind in the debates concerning free will and moral responsibility, is the view that the past guarantees the future (such that from any moment in time there is only one total way that things can play out from that moment on: the way they end up playing out). Consider the following loose argument for Chronological Determinism, which bypasses details and controversies I go into elsewhere.

First, clearly the entirety of what is going on at any given moment (the entirety, that is, of everything physical or spiritual or supernatural or eternal or whatever else there might be at that moment) all by itself brings about the entirety of what goes on next. Reality as it is now brings about reality as it is next—indeed, reality as it is now does so all by itself because we are talking about the entirety of reality as it is now (in which case any candidate “helping hand” presumed to be beyond reality as it is now, any supposed outside contributing factor involved in bringing about reality as it is next, already belongs to reality as it is now). Second, we all agree as well that if A all by itself brings about B and B all by itself brings out C and C all by itself brings about D, then it follows ultimately that A all by itself—albeit by means of B and C—brings about D. When we bring these two rather uncontroversial points together, what do we get? Well, it follows that the entirety of what is going on at any given moment (say, a moment ten billion years ago) all by itself brings about the entirety of what is going on at every subsequent moment (such as right now). That is all that Chronological Determinism says: the way reality is in the future is completely a function of the way reality was in the past, whether that past goes back to a first point (a big bang or God, say) or whether that past goes back endlessly.

Absolute Necessitarianism, which is a form of Determinism that contemporary metaphysicians typically consider a nonstarter (given its radical collapsing of all modal distinctions), is the view that there is an ultimate reality that necessitates itself and everything else (such that nothing is the case unless it is necessarily the case). Consider the following loose argument for Absolute Necessitarianism, which bypasses the details and controversies I go into elsewhere.

Assume that R is the collection of all things that do not provide the sufficient explanation for their own existences—things, in short, that are not self-caused. Assume, to put it another way, that R is the collection of all things that do not exist by the necessity of their own natures—that do not have existence, so we might say, baked into their essence (the way that being male, say, is baked into the essence of bachelor or having three interior angles is baked into the essence of a triangle). Clearly there must be a sufficient explanation for R—an explanation for each part of R and for why R obtains as opposed to some other collection. Why? Well, everything has a sufficient explanation for why it is—nothing, after all, comes from nothing. Suppose, then, that S provides the sufficient explanation for R. Now, either S is self-caused or S is not self-caused. As it turns out, S must be self-caused. Why? Well, to suppose that S is not self-caused entails a contradiction. After all, since S would be self-caused were it beyond R, the only hope for S not being self-caused is that S is either R itself or some part of R. But since S provides the sufficient explanation for R, S provides the sufficient explanation for itself—and so is self-caused—no matter whether S is R itself or some part of R. So one thing is for certain, as we have seen: S is self-caused. As self-caused, S exists by necessity—absolute necessity, in fact (since it has no dependence on anything else for its existence). Now, the necessity of S transfers over to that for which it provides the sufficient explanation: R and everything that makes up R. Why? Well, what is sufficient for something (call it “o”) is what fully explains why o does rather than does not obtain. But what fully explains why o does rather than does not obtain is what guarantees o. So since S is guaranteed (by its own nature as self-caused), it also guarantees what it provides the sufficient explanation for, which is R and everything that makes up R. The necessitarian implication should be clear. Since R and everything that makes up R are the only realities beyond that which exists necessarily in virtue of being self-caused, everything exists necessary.

Those who reject Chronological Determinism and Absolute Necessitarianism typically attack the key principle undergirding them: the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR). This principle, however, is the one thing on which I am unwilling to budge. I think of myself as an open person, but the PSR is a metaphysical hill on which I am prepared to die. Consider the following loose argument for the PSR, which bypasses the details and controversies I go into elsewhere.

The PSR says, in short, that you cannot get something from nothing. That, in effect, there is nothing uncaused, nothing that lacks a complete explanation, seems unquestionable. It is absurd to say some reality—some energy, some process, some thought, some action, some hallucination, some quantum fluctuation, or so on—can bloom from the absence of all reality. Only something going on can engender something going on. That is the main case for the PSR. The difficulty of spelling the argument out in steps (as I did it for example when defending Chronological Determinism) is a function of the fact that the PSR is so basic that it would be presupposed in every step—presupposed in the very nature and point of the argument. On this note, however, consider—in what amounts to an indirect reinforcement of the certainty of the PSR—that any argument against the PSR tries to give a sufficient reason for rejecting the PSR and so seems to assume that for something to be the case—in this case, that the PSR is false—there must be a sufficient reason why it is the case. Any argument against the PSR seems to assume, in short, the PSR. Furthermore, it is impossible even to imagine something—say, a potato or a car—coming from nothing. To do so would require doing what is beyond our reach: namely, imagining as absent every possible sort of cause for that thing, including—and here is the nail-in-the-coffin point—causes for that thing that we could not even imagine. Besides, there is no way that beings coming from nonbeing can ever be demonstrated experimentally, for obvious reasons. No matter what pop interpretations of quantum mechanics might say, uncaused events have never been—and could never be—demonstrated. As Einstein (perhaps one of the most famous recent advocates of the PSR) would put it: any scientist who says that a certain particle E lacks a sufficient cause could never be sure of what it is more reasonable to assume anyway: that there are variables operative beyond their ken.

3. Why the Incompatibilist Premises are True

The second premises of the HCD Argument and the HAN Argument are, in effect, forms of incompatibilism. The second premise of the HCD Argument says that human moral freedom is incompatible with the truth of Chronological Determinism and the second premise of the HAN Argument says that human moral freedom is incompatible with the truth of Absolute Necessitarianism. Why think that such forms of incompatibilism are true?

Much effort has been devoted to defending these forms of incompatibilism. The basic point is rather obvious.

If whatever I do or think or feel or so on is necessitated by (or, to put it in the colorful way that my students tend to remember, shit completely out of) the remote past before I was born (in the case of Chronological Determinism), then clearly whatever I do or think or feel or so on is not ultimately up to me. And if whatever I do or think or feel or so on is necessitated by some self-necessitated source such as God (in the case of Absolute Necessitarianism), then clearly whatever I do or think or feel or so on is not ultimately up to me. But if whatever I do or think or feel or so on is not ultimately up to me, then I lack moral freedom (the sort of freedom on which moral responsibility depends).

Since I have yet to make a longer post in defense of these forms of incompatibilism, let me make the case here in a more careful fashion. To streamline the discussion, I will talk simply in terms of our actions. It should be clear, however, that what I say applies as well to our thoughts and our feelings and our physical characteristics and our cognitive abilities and our personalities and so on.

1. If Chronological Determinism is true or Absolute Necessitarianism is true, then our actions are guaranteed by what we ultimately have no control over occurring.

Rationale.—We ultimately have no control over whether conditions that precede our very existence occur (obviously). But our actions are guaranteed by a past that precedes (temporally, perhaps ontologically as well) our very existence if Chronological Determinism is true. And our actions are guaranteed by a chain of necessitation that stops at a self-caused wellspring that precedes (ontologically, perhaps temporally as well) our very existence if Absolute Necessitarianism is true.

2. If our actions are guaranteed by what we ultimately have no control over occurring, then we ultimately have no control over whether we perform our actions.

Rationale.—If p occurs and we ultimately have no control over whether p occurs, and if p’s occurrence guarantees q’s occurrence and we ultimately have no control over whether p’s occurrence guarantees q’s occurrence, then q occurs and we ultimately have no control over whether q occurs. For example, if my not lifting the pen right now is guaranteed by what I ultimately have no control over, then I ultimately have no control over whether I lift the pen right now.

3. If we ultimately have no control over whether we perform our actions, then our actions are not free (free in the sense required for moral responsibility).

Rationale.—S does action A freely only if S ultimately has—at least the merest sliver of—control over whether A happens.

Therefore, if Chronological Determinism is true or Absolute Necessitarianism is true, then our actions are not free.

Those who reject the forms of incompatibilism in question do not typically go after premise one or premise three of the argument I just gave. That makes good sense. Premise one is indubitable. After all, (a) the past goes back before we came to be (in which case our actions are guaranteed by what is ultimately not up to us if Chronological Determinism is true) and (b) we are not deities existing by the necessity of our own essences (in which case our actions are guaranteed by what is ultimately not up to us if Absolute Necessitarianism is true). Premise three also seems unquestionable. After all, how can our actions be done freely, freely in the sense that we are subject to praise or blame for those actions (and so in a sense independent of any pragmatic considerations), if ultimately we lack even the merest say over whether the action takes place? Sure, even if we lack the merest say over whether the action takes place we are still free in the nonmoral sense that, say, we have more range of possible behaviors than a tree or a stone. But clearly we are not morally free if we ultimately lack even a modicum of say over anything we do.

Compatibilists do attack premise two, however. Using merely the language of Chronological Determinism (in order to streamline the discussion), here is how the compatibilist’s case typically unfolds.

Even if it is guaranteed from the remote past that I do not lift the pen at time T1, it might still be that I ultimately have control over whether I lift the pen at T1. How so? (1) Even if my not lifting the pen at T1 has been guaranteed by the remote past over which I have no control, I still ultimately have control over whether I lift the pen at T1—so long as I would have lifted the pen had I tried. (2) Even if my not lifting the pen at T1 has been guaranteed by the remote past over which I have no control, I still ultimately have control over whether I lift the pen at T1—so long as by not lifting the pen I am doing what I want to do and no one is coercing me (say, through hypnosis) not to lift the pen.

I will end by giving the standard incompatibilist responses to these points, responses that I find more than convincing.

First, if Chronological Determinism is true and S’s not lifting the pen is guaranteed by the remote past (such that it has been guaranteed that S does not try to do otherwise than what he does), then S ultimately does not have actual control over whether he lifts the pen (however much counterfactual control he may have). Second, if everything that happens is guaranteed by the remote past prior to the birth of S, then not only S’s action but also the desire to do the action itself is guaranteed by the remote past prior to the birth of S. In this case, even though S is doing what he desires, the action resulting from this compelled desire is still unfree. The coercion by the remote past, moreover, is more unescapable than any hypnosis or gunpoint threats! Actions resulting from being controlled by an alien force (as in hypnotism by a divine hypnotist) are actions that S does not do freely. But actions guaranteed by the past are relevantly similar to, and at least as compelled as, actions resulting from being controlled by an alien force. (The same points apply, of course, when we put the debate in the language of Absolute Necessitarianism.)

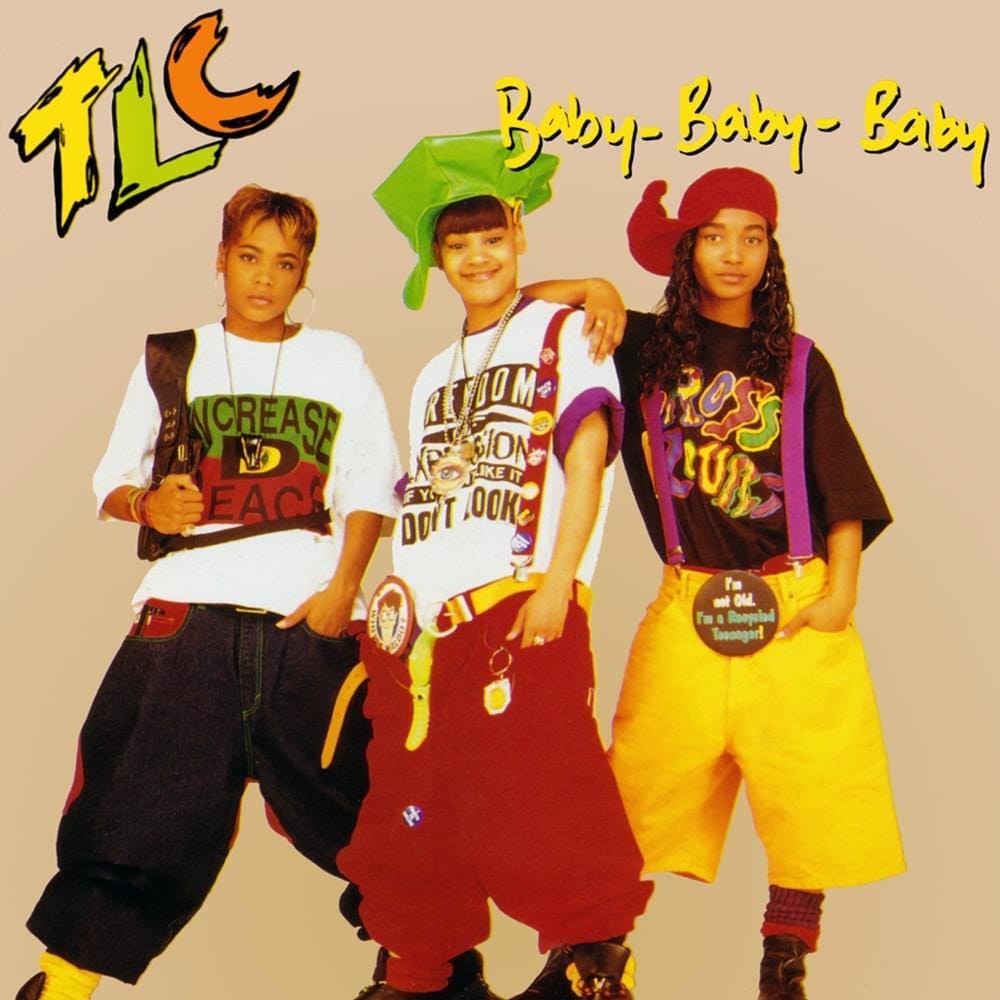

As this response makes clear, there are two key reasons why the compatibilist attack fails. (1) Having actual-factual control (one cannot but think of Chilli from TLC here: “Baby that’s actual and factual”) is required for morally free behavior. Counterfactual control, which I do admit we do have, is not enough. But if Chronological Determinism is true or Absolute Necessitarianism is true we do not ultimately have that actual-factual control. (2) An action being (a) uncoerced (in the court-of-law sense) and (b) in line with the agent’s desire still does not mean that the action would be morally free in a reality where either Chronological Determinism is true or Absolute Necessitarianism is true. For the agent would still be coerced—indeed, in an even more potent way than the typical cases we talk about in the court of law (hypnosis, gun-point threat, addiction, mental illness)—and the agent’s desire to do the action would be as beyond the ultimate control of the agent as the action itself if Chronological Determinism is true or Absolute Necessitarianism is true.

This piece is unpublished

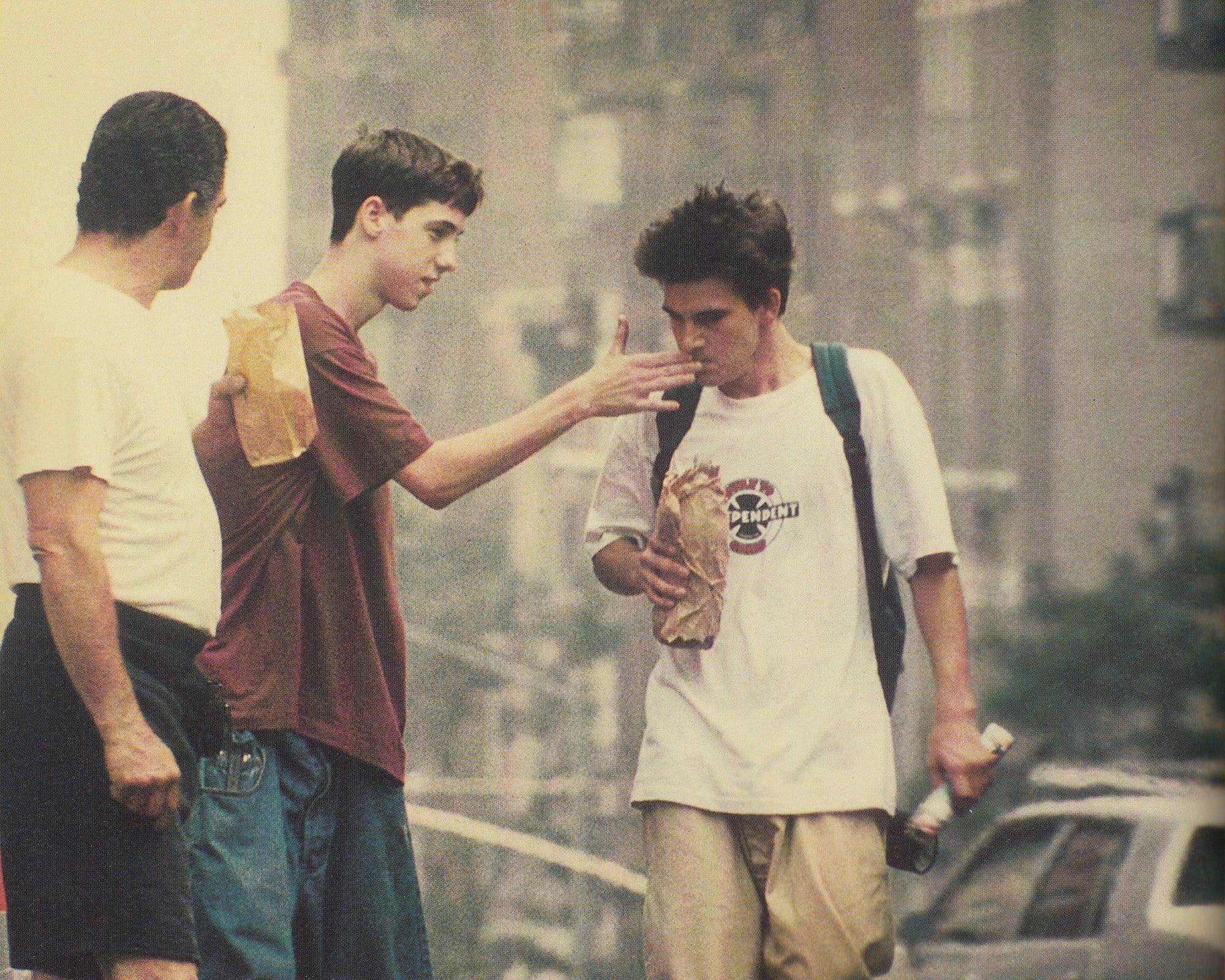

Photo: Remember exactly where I was when this film, Kids, first came out—it so well captured how we were living and the music that was coursing through the air: informlibrary.com/Kids-Larry-Clark